Most of the Free Association crew have just returned from Heiligendamm and the counter-mobilisation against the G8 summit and it’s worth jotting down a few thoughts whilst the memories are still fresh. (When I say most of us have returned, I don’t mean some are still on German soil, languishing in some prison cell; just not all of us went in the first place.)

First, the overall assessment. One of us has a 4-year old son who ranks good things as follows: cool, wicked, awesome, bring it on, kerchow. On this scale we agreed the Heiligendamm summit protest was awesome. The front-page headline in the left-of-centre Die Tageszeitung — reporting on the summit’s opening day — was ‘G8 successfully blockaded’. According to the Financial Times our ‘protests tipped the G8 summit into logistical chaos’. The FT reported ‘overwhelmed police forces’ and ‘lines of exhausted riot police streaming out of the area in the early evening, some of them with stitches and black eyes, as formations of helicopters roared overhead. “I’ve never seen anything like this,” said one officer.’ (‘Marauding clowns and squabbles embarrass organisers’)

In a great piece, which hopefully Red Pepper will publish, our friend and comrade Ben, of the FelS (the Sha La La Communists), describes every road into the Red Zone being blockaded for the better part of 48 hours, from 11am on Wednesday 6 June, the summit’s opening day, until 11am on Friday, when blockaders voluntarily began to disperse (en masse) in order to reassemble for a massive demonstration in Rostock. Summit organisers were forced to resort to plan B, which involved using helicopters to airlift many delegates, whilst journalists and others had no choice but to travel by sea, facing huge delays. We heard reports that even this plan was disrupted by blockades of ports/ferry terminals in Rostock; apparently on the first day of the summit many delegates were advised to remain in their hotels. And according to some reports, only four journalists made it to the opening ceremony. Oh yes, and the Japanese PM was delayed at the airport as he arrived. (By yet another blockade-cum-demonstration; not because he was hanging about by the carousel waiting for his baggage.)

This was certainly a victory and the most successful protest against a major summit ever. In fact, I wonder whether the Heiligendamm summit protest is to the G8 what Seattle was to the WTO. Seven years after that crazy November day in 1999, the latest round of trade negotiations — the Doha round — faltered and collapsed. The WTO now seems to be defunct. The Seattle protest and the social movements which formed around it and of which it was a part played a vital role in that. My guess is that the G8 leaders and political strategists are desperately looking for a way out of their annual shenanigans. Probably, there’s been a gnawing anxiety about their summit for a few years now, but our almost victory this month will have made them even more desperate. Because, the G8 summit is about legitimising neoliberal globalisation. An overriding message from Heiligendamm was that the G8 and neoliberalism is illegitimate. No doubt they’ll meet as planned next year in Japan. Probably they’ll meet in Italy in 2009 too, though that one will be tricky, being both the 10th anniversary of Seattle and the first Italy-hosted summit since Genoa. (That venue has already been decided: a small island in the Mediterranean Sea; not Elba, where the French emperor Napoleon I was exiled in 1814, but maybe the effect will not be so different.) But then… who knows, but I doubt very much that the G8 will exist in its current form.

Of course, they’ll spin it. They’ll talk of making their meetings more effective, perhaps they’ll have biannual meetings but on a much smaller scale with little publicity. They’ll use the comments of Helmut Schmidt, cofounder of the G6 (as it then was) in 1975, who’s criticised the current summits as a ‘media circus’ or something similar. But whatever they say, we should remember: it was us that done it. Or, as we wrote in ‘Worlds in Motion’: ‘sometimes it’s hard to see the social history buried within the latest government announcement.’

So, no doubt about it, Heiligendamm was a victory for us. It really is important to stress this. Many reports, particularly in the UK, adopt a top-down approach. The mainstream media tends to focus on what happened or did not happen inside the Red Zone — that piece in the FT was something of an exception. Indymedia seemed to more interested in reporting on repression and decentralised actions than the mass blockades. The following response to my comment that Heiligendamm was a victory to us is interesting.

i find this a bit offensive. how was it a victory?

maybe you enjoyed yourself, but i don’t think the kids of bangladesh were cheering. nothing changed; ergo, no victory.

Let’s leave aside the implicit racism of the comment — it homogenises the ‘kids of Bangladesh’ and assumes that ‘they’ are less politically sophisticated than ‘us’ (if I can cheer the victories of others, recognising them as part of my struggle, then why can’t they cheer my victories? — and the author’s quickness to take offence. It nevertheless raises at least two important questions.

First, did anything change? If so, what and how? Second, how does the mobilisation against the G8 in Heiligendamm relate to struggles elsewhere, e.g. in Bangladesh. I.e. how do antagonisms articulated locally become global? Or, perhaps these local antagonisms are immediately global. If so, then how do we understand them as such? Third, in exactly what sense was Heiligendamm a victory? (That hoary chestnut again: what does it mean to win?)

There are probably several reasons why it was a victory and why something changed.

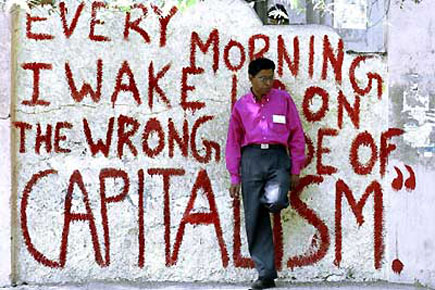

1. Our mobilisation was a massive demonstration that the G8 and neoliberal globalisation is illegitimate. With neoliberalism already struggling for legitimacy, this is important. Though, as Rodrigo points out, it’s probably true that global capital can continue to reproduce itself without legitimacy for some time.

2. We produced the affect of victory. Of course I enjoyed myself! How could I experience those feelings of collective power and not enjoy myself? And I’m sure thousands of others did too. This is great. These feelings will remain with us and give us the confidence and optimism to continue acting. Whcih increases our power. So the ‘affect of victory’ isn’t just about ‘feelings’; it’s about material forces.

(And conversely (tho’ arguably) our enemies probably returned home without any affect of victory. Yes, they were reasonably successful in producing a spectacle of victory — more successful in some countries than others — but journalists were pissed off at having to spend so long on boats and queuing for boats, delegates’ helicopters had no proper landing places (and it’s undignified for a dignitary to have to wade through long grass) and the food and wine ran short! To top it off, delegates fought a lot amongst themselves. I’m not sure how important this all is. I think it’s probably less important whether Bush or Merkel experienced an affect of victory or not. But perhaps it matters when we’re talking about journalists and others essential for producing the summit as its organisers would wish. In Heiligendamm, it was very clear that the real energy was located with us. And energy is attractive! I’m sure journalists reporting on our blockades enjoyed a far richer experience and I think that’s important.)

3. We demonstrated very clearly — both to ourselves and people observing around the world — that mass actions can be effective. Again, this confidence in our own power is enormously important.The question of the relationship between local and global antagonism is harder. Tadzio (in his letter) makes a great point about this:

we failed to construct a clear antagonism because we were playing on different laying fields. concretely: while our protests were a mere police matter (a clear antagonism certainly existed between cops and demonstrators, as all of us who were beaten, arrested, tear-gassed, water-cannonned can surely attest to), the legitimation of the summit occurred on the discursive field of talking about climate change. now, the german radical left almost completely lacks a good political story about climate change, one that goes beyond individual appeals to fly less, raises the question of property and capital, while at the same time giving suggestions for how to act (the latter being a crucial component of every good political story).

7-8 years ago, when summits’ headline issues were still very much trade, privatisation, ‘the neoliberal agenda’, we had an excellent counter-story. our militant actions were embedded in this counter-story, so that our actions could rise beyond being mere policing matters, to being explicitly political, because they directly interfered in the construction of the discursive field that was being built to legitimate global authority. today, we have no story to counter theirs, so this production can go on undisturbed, no matter how effective our blockades are. it may be responded at this point that issue-engagement with the summit’s headline issues would add to the legitimation of an institution we try to delegitimate, but i think it’s fairly obvious that this year’s refusal to really construct a counterstory didn’t lead to a greater delegitimation of the G8.

thus the action point of this particular political story: we in the german radical, autonomous, anticapitalist left (whatever you want to call it) need to work to come up with a good story about climate change, to break through the relegitimation strategies so effectively deployed by merkel. more generally, at summits, we need to work in advance to develop a punchy story that relates to the summit’s headline issues, within which we can embed our actions. otherwise the latter remain mere public order problems, and cannot interfere with the production of global authority as legitimate.

The Heiligendamm mobilisation was also notable for two other important questions.

First, violence. (Not really a novel question, I know.) In some ways, I wonder whether the movement has gone backwards here. One of the exciting aspects of Heiligendamm (and what made it different from and more successful than Gleneagles in 2005) was the hard-won coalition of 120-odd groups that was the Block G8 campaign. But this coalition threatened to implode after the mini-riot in Rostock on Saturday 2 June. Simon makes some good points about this, talking of media (both corporate and IMC) hyperbole and of people reverting ‘to type’. Dorothea also said something really good. She said she’d learned long ago that denouncing certain protesters as ‘violent’ is never helpful. This links to Simon’s point, of course. Denunciation is about definition, it’s about closure, it’s about limiting our movement. Reverting to type is about stasis. But changing the world requires movement.

But, as Simon goes on to say, between Saturday and Wednesday, ‘the turnaround was amazing — because of the success of the blockades — and their fluidity and diversity. If you wanted a ruck, find the blockade where it was happening and contribute. If you wanted to keep a more tranquil blockade going overnight, you could find out where to go. Diversity and working together was again OK.’

Second, the tension between different modes of decision-making. The success of the Block G8 blockades depended on a closed group with a secret plan. This group did a brilliant job in getting thousands of people from the Rostock camp to the North gate and thousands more from the Reddelich camp to the East gate (by Bad Doberan). Our departure time, our route, our exact destination all had to be kept secret. How else could our objective of getting onto the key roads into Heilgendamm have been achieved otherwise?

Some people were very dismissive of Block G8 for this: ‘I’m an anarchist, I’ll not follow anyone, I’ll do my own thing. Fuck Block G8’. One person wrote on Indymedia: ‘Block G8 was a very hierarchical organisation. In the meetings I went to, all the details of the action were being organised by “action councils” and seemed very unaccountable and inaccessible unless you were prepared to go along and be cannon fodder for a central organising committee.’ As somebody responds on Indymedia, this is ‘quite disrespectful of those who had put huge effort and time into organising things (which are usually illegal, and enormously stressful, and done at great potential personal cost). I was really happy that some people had thought beforehand extremely carefully about to get us from camp to blockade in a coordinated way.’

But, getting thousands of people from camp to road is one thing. Maintaining a successful blockade once there is something else. The Block G8 secret ‘action committees’ did a great job getting us all onto the road and I was happy to follow them there. But sustaining the blockades required participation by all the blockaders and consensus decision-making, and Block G8 were reluctant to give up their power. So at the East gate we suffered a number of highly frustrating meetings on Wednesday evening, as the Block G8 action committee dominated discussions — taking full advantage of their ‘ownership’ of megaphones and the sound system and of the authority they’d won through their successful leadership in getting us onto the road. In short, they behaved like arseholes, accusing anyone who disagreed with them of attempting to destroy the ‘action consensus’ and of being intent only on ‘escalation’. At one point, they suggested that if they didn’t get their way, the blockade would no longer be under the auspices of Block G8 — this was a despicable attempt on their part to delegitimatise our action, which would have made it easier for the state to repress and criminalise. In fact, the blockade was in danger of falling apart altogether as Block G8 claimed that we’d achieved our objective and ordered a retreat. This retreat was halted only when two people sat down in the road in front of the sound system to prevent it leaving: blockading the blockaders!

Tensions within the blockade. Frustration with Block G8 and their tactics. The unsettling experiences of giving up a location we’d become familiar with to retreat 200m down the road and of watching many groups of people drift away altogether. Nervousness as darkness fell: the fear we’d be rudely awakened at 3am by water cannon and, possibly, tooled-up riot cops (combined with the more prosaic worry that tarmac doesn’t make for the best of beds). Wednesday night was somewhat tense! (It was important to bear in mind that although darkness presented uncertainties for us, it did so for the police too. They were exhausted too. They had no idea what we or some of us would do in the night — we were, after all, literally metres from the fence encircling the Red Zone. If they attacked, how would be react — and not only were we near the fence, we were right next to a railway line, with its plentiful supply of fist-size ammunition. Much safer for them to hold off. But this is exactly why we needed to maintain our collective identity and this is why the behaviour of Block G8 was so dangerous.) In the event, the night passed uneventfully, though some of our fears were realised: our numbers seemed to have dwindled from several thousand to fewer than one thousand. Thursday morning brought some great coffee — artisan-brewed latte from a wonderful man in a van operating two tiny expresso pots and a saucepan on a tiny stove — and more frustration courtesy of Block G8, who again suggested we’d done enough and that it was time to leave. But this time, we’d really had enough: a couple of organised and collective-minded affinity groups with experience of consensus decision-making challenged their leadership and we enjoyed a couple of fantastic blockade-wide spokes-meetings. As a result, our collectivity was reestablished and the blockades at that gate lasted for another 24 hours.

So, two points here.

First, how can we learn to shift between these two modes of decision-making — on the one hand, having a secret plan put into action by a closed group, and on the other, open, horizontal consensus decision-making — more smoothly, without rupture and discord?

Second, our experience on that blockade shows again the importance of affinity groups. Not only for dealing with the state, but, as there, for having the ability to override Block G8’s action committee which had outlived its usefulness.

That’s enough criticism of Block G8 and I want to end on a more positive note. Their advice as we headed for the road on Wednesday morning was spot-on and expresses our politics perfectly:

Don’t run straight at the cops; aim for the gaps!

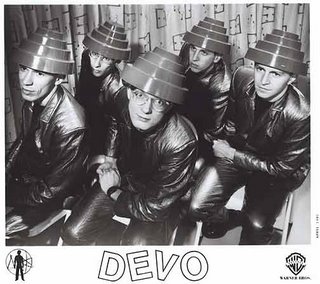

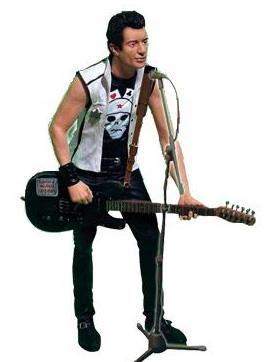

A new year arrives, we have a new project to be getting on with and I should be concentrating on that but I just can’t stop my head from turning backwards. To be more precise I can’t stop musing on those moments when music and politics collide and the effect they’ve had on my life. This was all sparked off by one of my Christmas presents: “The Future is Unwritten”, a documentary about the life of Joe Strummer. I found it pretty affecting. There was the recognition of similar experiences (to some extent) but more than that was a realisation of just what an inheritance the sensibilities of that history have been. I was powerfully struck by how the refrains re-ignited by watching that film had structured the territory upon which I’d lived out my life. Even Strummer’s vision of heaven as a series of campfires, that we are drawn towards and drift between, struck a real cord. Taking me right back to formative trips to 1980’s Free festivals.One of the things it sparked of in me was the re-occurrence of a sense of shared alternative history, formed out of collective experiences; political, musical or both. It’s a sort of minor history, in that it’s deviation from the standard history but I was reminded just how virulent and widespread it is. It might be a history that’s only sporadically actualised but it’s no less real than one David Starkey might write about. That sense of a history was amplified by stumbling across blogs like

A new year arrives, we have a new project to be getting on with and I should be concentrating on that but I just can’t stop my head from turning backwards. To be more precise I can’t stop musing on those moments when music and politics collide and the effect they’ve had on my life. This was all sparked off by one of my Christmas presents: “The Future is Unwritten”, a documentary about the life of Joe Strummer. I found it pretty affecting. There was the recognition of similar experiences (to some extent) but more than that was a realisation of just what an inheritance the sensibilities of that history have been. I was powerfully struck by how the refrains re-ignited by watching that film had structured the territory upon which I’d lived out my life. Even Strummer’s vision of heaven as a series of campfires, that we are drawn towards and drift between, struck a real cord. Taking me right back to formative trips to 1980’s Free festivals.One of the things it sparked of in me was the re-occurrence of a sense of shared alternative history, formed out of collective experiences; political, musical or both. It’s a sort of minor history, in that it’s deviation from the standard history but I was reminded just how virulent and widespread it is. It might be a history that’s only sporadically actualised but it’s no less real than one David Starkey might write about. That sense of a history was amplified by stumbling across blogs like