Every action has the status and the mannerisms of a quotation.

Paolo Virno, Déjà Vu and the End of History

I’ve been meaning to follow up on Keir’s post about the “explosion of sincerity” for weeks now, so here are some threads I’m trying to pull together…

In Déjà Vu and the End of History Virno talks about how we appear to be living through an era of hyper-historicity, trapped in a pattern of permanently recycling and reworking everything. On a superficial level we can point to the ceaseless cultural regurgitation that’s symptomatic of postmodernism: from Mad Max to TFI Friday to this bollocks, there’s no end to retromania (and if I tried harder, I could probably think of something that’s actually a re-make of a re-make). But Virno also makes reference to the Society of the Spectacle, the idea that we collect our own lives while they are passing: the present is duplicated as the spectacle of the present and we end up watching ourselves live. This has real consequences. As Virno puts it:

The state of mind correlated to déjà vu is that typical of those set on watching themselves live. This means apathy, fatalism, and indifference to a future that seems prescribed even down to the last detail.

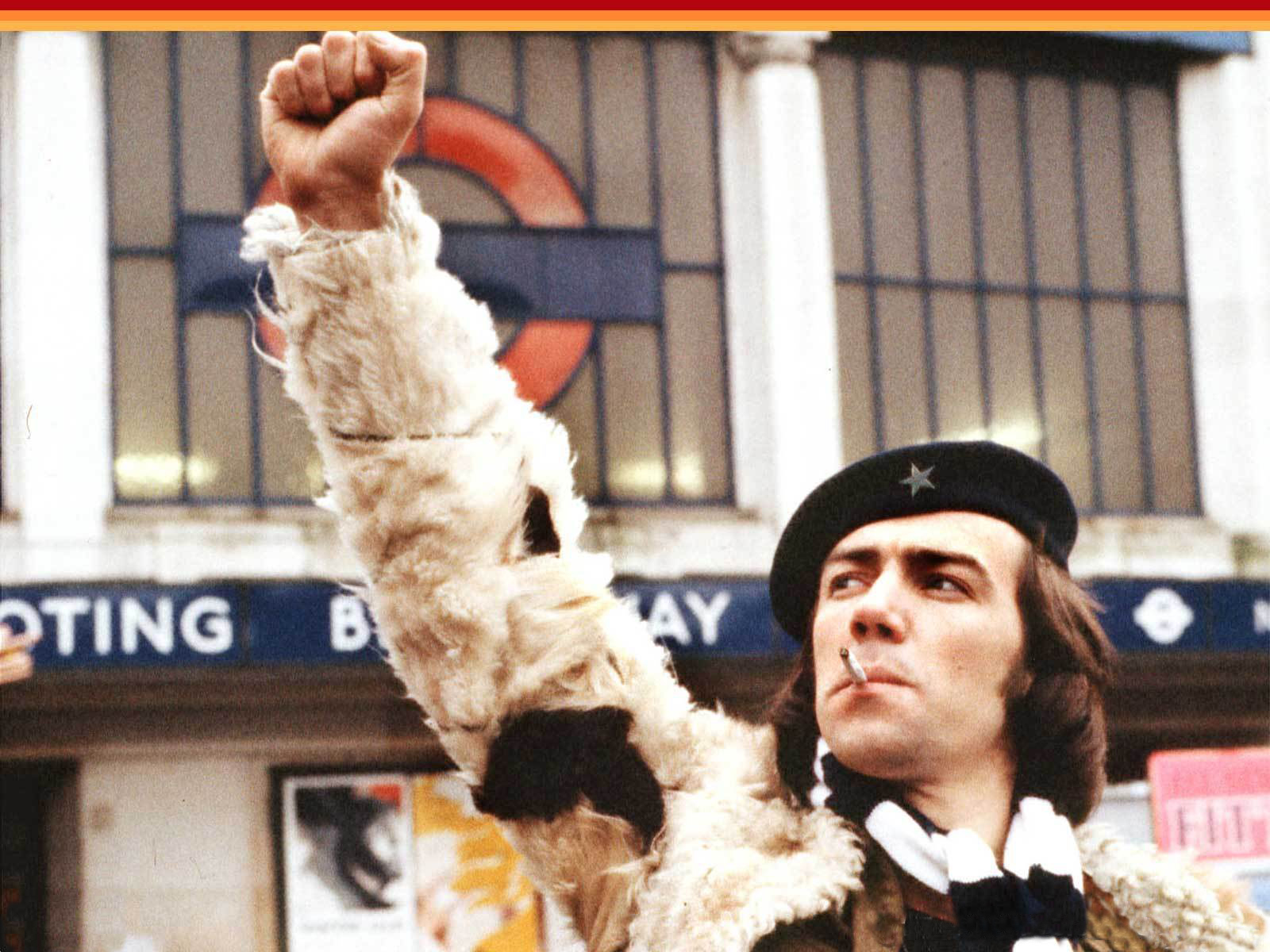

Years ago I can remember Crass singing “Big Brother ain’t watching you mate, you’re fucking watching him!” At the time I thought it was prescient, predicting the switch from the Panopticon to TV as a system of control, but now it feels antiquated. Yes, neoliberalism unleashed whole new levels of surveillance and micro-management, but those rules have been internalised, incorporated (increasingly written into our bodies). It’s not that we’re watching Big Brother – we’re watching ourselves.

It’s easy to read this hyper-self-awareness as an inevitable outcome of the digital age: an existence played out on social media is almost the very definition of watching yourself live. But it’s probably more accurate to see this as part of a wider metropolitan, post-modern subjectivity. Or at least that’s what I get from Virno’s talk of a “mannered life”. And that mannered life, in turn, is bound up with a hyper-historicity, a sense that both the future and the past have been collapsed into a never-ending “now”.

What the fuck has this got to do with political organisation? Well, the idea of a never-ending “now”, one without meaningful past or future, was elsewhere expressed as the “end of history”: the notion that capitalist liberal democracy represented the endpoint of political evolution. There Is No Alternative. And the crucial thing about TINA was that we weren’t ever required to believe it. We didn’t have to follow Thatcher, or Reagan or any neoliberal ideologues. Because the end of history also meant the end of ideology. TINA was not an article of faith, in that sense. Instead we would come to incorporate it in the material of our daily lives just by acting as if there was no alternative. Job done.

The end of history theory was always bullshit, of course. Intellectually, it made no sense. But politically it became kind of self-fulfilling. And it still captures a lot of the impasse we find ourselves in today, eight years after the worst crisis in capitalist history. On the face of it, you’d expect a massive increase in social unrest in the aftermath of 2007-08. And yet that hasn’t happened, certainly not in the UK and hardly at all in the rest of Europe. Sure, Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain are both hinting at a different way of articulating the relationship between social movements and electoral politics, but they still appear exceptional: nowhere have we really seen the kind of sustained civil conflict that our bosses feared. On the other hand, there’s no shortage of “apathy, fatalism, and indifference to a future that seems prescribed even down to the last detail”.

At our comedy talk in Leicester we tried to think this through by talking about the “hyper-ironisation” of contemporary culture. We suggested that one way we protect ourselves against heightened levels of risk is by adopting a posture of cynical irony. We don’t invest too much of ourselves in anything (or when we do, we reserve the right to say “Ah well, it’s all shit anyway” if things don’t work out as planned). In Leicester we started to use ‘hipster culture’ as a kind of shorthand for this. It’s an easy target precisely because that Hoxton-beard-skinnyjeans-fixie cliche is a near-pastiche of this modern sensibility (and one that’s always been open to ridicule). But it’s more important to see this posture of cynical irony as a default position for almost anyone wanting to get by in the modern world. It’s a stance which isn’t restricted to a particular subculture, lifestyle or generation. As the writer David Foster Wallace put it:

lazy cynicism has replaced thoughtful convictions as the mark of an educated worldview

While lazy cynicism offers some protection against the fragility of modern life, it does so by eliminating the possibility of things like ‘conviction’ and ‘commitment’. It makes sincere statements of belief both hard to express and difficult to take seriously. It militates against developing any kind of revolutionary subjectivity.

But as we know, history doesn’t simply end. Every now and then, the past and the future that were meant to be off-limits get thrust centre-stage and people start to build different worlds. The global social movements of 2011 that were sparked by the Arab Spring are a prime example. Lazy cynicism gave way to something else – “an explosion of sincerity”.

We mean it, maaan!

Maybe the meaning of sincerity here is obvious: it’s the opposite of a cynicism that can take many forms, from a weary knowingness to nihilistic detachment. But it might also be useful to counterpose sincerity to two other values: authenticity and truth.

If our mode of existence is so mannered and studied, perhaps what we should be striving for is some form of authenticity as a way out. After all, what could be more sincere than expressing ‘the real me’? But we should tread carefully here. The injunction to “be yourself”, to become what it means to be truly you, is a central part of the modern neoliberal narrative. And neoliberalism prides itself on its ability to accommodate virtually every identity: step right up, there’s a pigeonhole for everyone (at the right price, of course). That taxonomic impulse simply reinforces our permanently heightened sense of self-awareness, further entangling us in regimes of vigilance and (self-) policing. A mannered life is one where we’re watching ourselves, watching others, forever checking… There’s also an individualising dynamic at work here – I’m only trying to find ‘the real me’ not ‘the real us’ – which undercuts attempts to create new forms of collectivity. At worst, it results in the kind of shopping-list identity politics which first emerged in the mid-1980s, or the race-to-the-bottom of privilege-checking.

On the other hand, if the dominant mode of being in the world is based on artifice, perhaps explosions of sincerity are bound up with truth. You don’t have to believe in the “wake up sheeple!” nonsense to see that some element of this seemed to be at work in the Occupy phenomenon. The idea of “the 1%” can be seen as a ‘hidden transcript’ which went public, creating the space for people to question power and begin to act out different conceptions of the world. The problem with this perspective is that hidden transcripts are caught up within the common sense of the world where they arise. They arrive with loads of baggage. The idea that there is a truth out there seems to fall into the same essentialist trap as the search for authenticity: both are more interested in the destination than the journey. (In fairness, you could argue that something similar lurks behind Virno’s claim that our actions appear as quotations – as if we just need to release them from the air quotes that enclose them. I actually think there’s more to Virno’s formulation than this, but whatever).

I’m going to stop here before I lose the thread completely. But I need to make one more note to self. When Virno talks about the hyper-historicity of modern life, he refers to “the excess of memory” and quotes Nietzsche’s aphorism that “all action requires forgetting”. In that sense, all meaningful action is a leap in the dark. Perhaps sincerity is a way of preparing ourselves for that. Those social movements which exploded in 2011 are not about authenticity or truth (which are both about correctness). Instead they are more to do with a certain openness: of mind, but also an openness of spirit, of heart. “We should talk of love not just capital”. Sincerity here indicates something like honesty and a willingness to let go (and in the act of letting go, to find new selves).