Pop culture has always fascinated us. Partly because popular music was the background to our lives growing up, but also because popular culture is an essential counterpoint to the (mostly) marginal political spaces we inhabit. And there’s a tension between the two. Sometimes they clash, sometimes they overlap, and sometimes – just sometimes – they pulsate together in the most incredible way, throwing new light on the past and revealing different visions of the future.

Recently we contributed to Notes From Technotopia, an exhibition in Bradford which pulls together a number of different artists who “offer different ways in which to think or dream about the future through the lens of past and present trends in technological development”. Our piece, Rediscovering Red Plenty, was prompted by our interview with F.A.L.C.O. where the singer mentioned the early ’80s Futurist Oi! band Red Plenty as an inspiration.

When a musician in 2015 makes a reference to a band from 1981, it pushes all our buttons: Gang of Four, Public Image, the Raincoats, Wire… they’ve all been cited recently. But Red Plenty? They were a band we’d vaguely heard of when we were growing up — and following punk and its various sub-genres — but had pretty much forgotten. Maybe F.A.L.C.O.’s singer stumbled over them while rifling through her dad’s record collection, but that wasn’t the whole story. Why would a record from that era resonate so much nearly 35 years later? So we decided to do some further digging.

We soon encountered a major problem: 1981 is pre-internet so there was almost nothing to see when we started googling the band. We had to switch to a more analogue route, hooking up with old mates, tracking down friends of friends, and trying to unearth people from a lifetime ago.

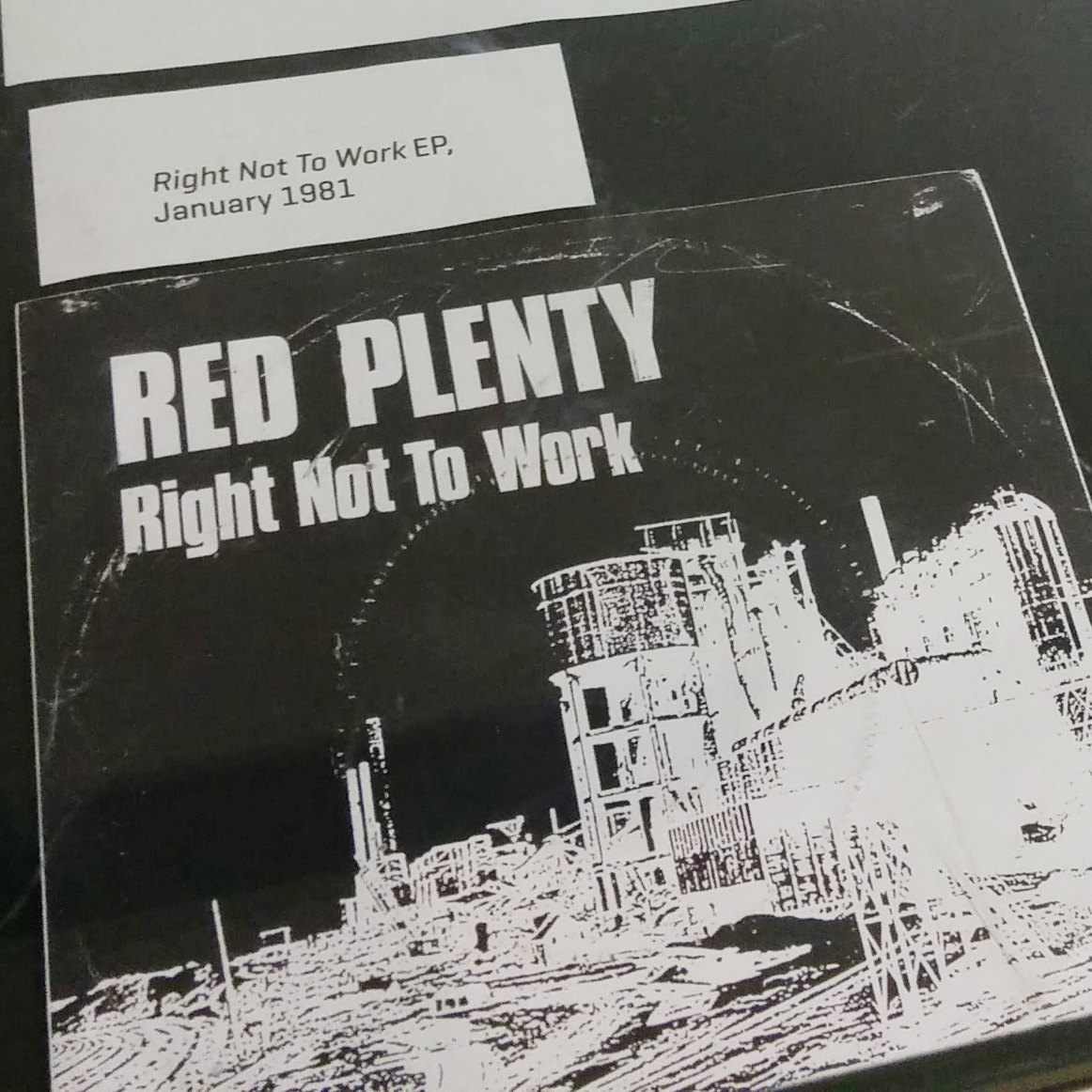

So here are the bare facts: as far as we can tell, Red Plenty were a four piece from Corby who produced just one four-track EP at the end of 1980 (‘Right Not To Work’, ‘Five Year Plan’, ‘Concrete Cow’, ‘New Future’). We found a few more tracks (‘We Want It All!’, ‘Assembly Line’ and ‘Ours Sincerely’) on a 1983(?) compilation tape but they don’t seem to be on vinyl anywhere.

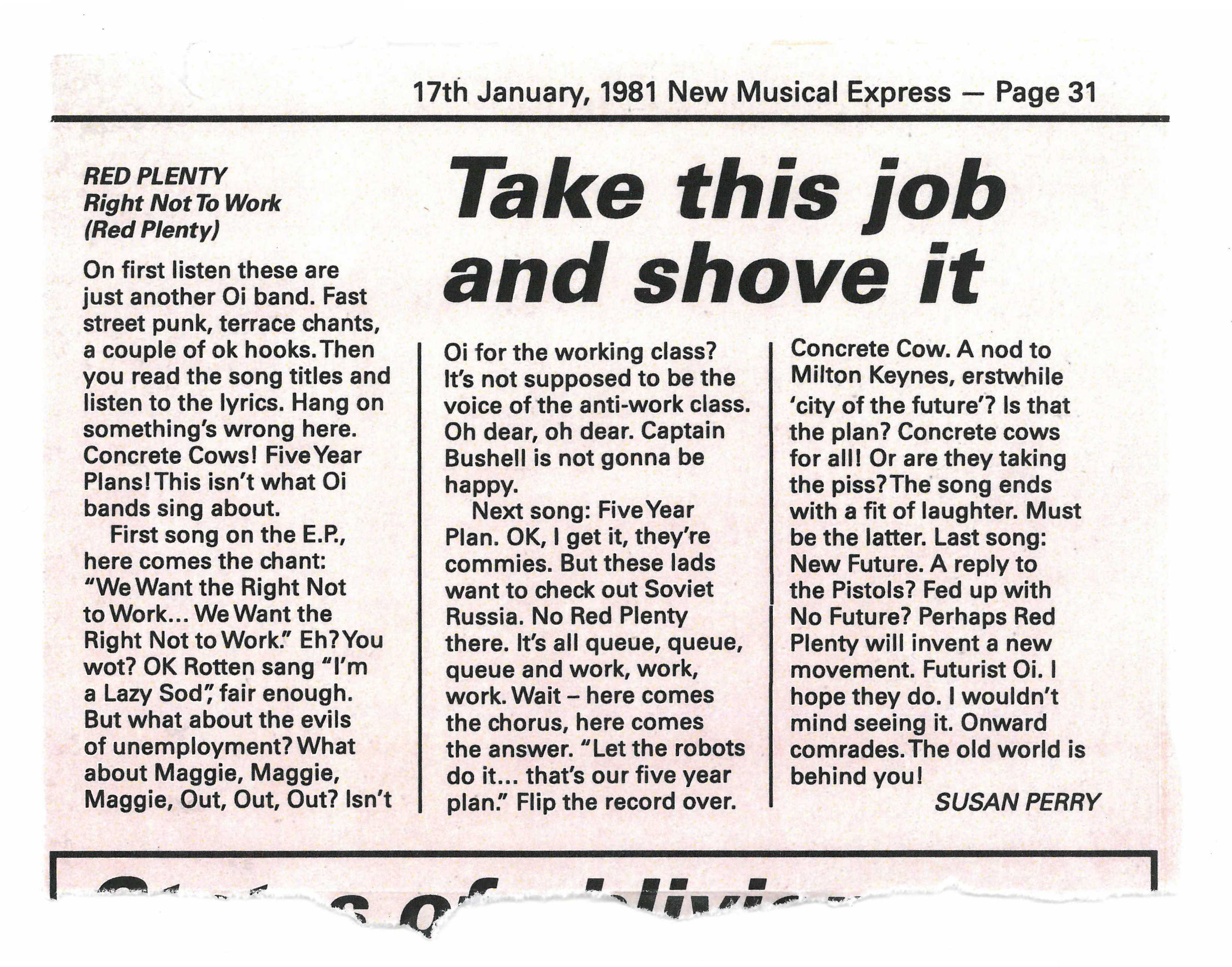

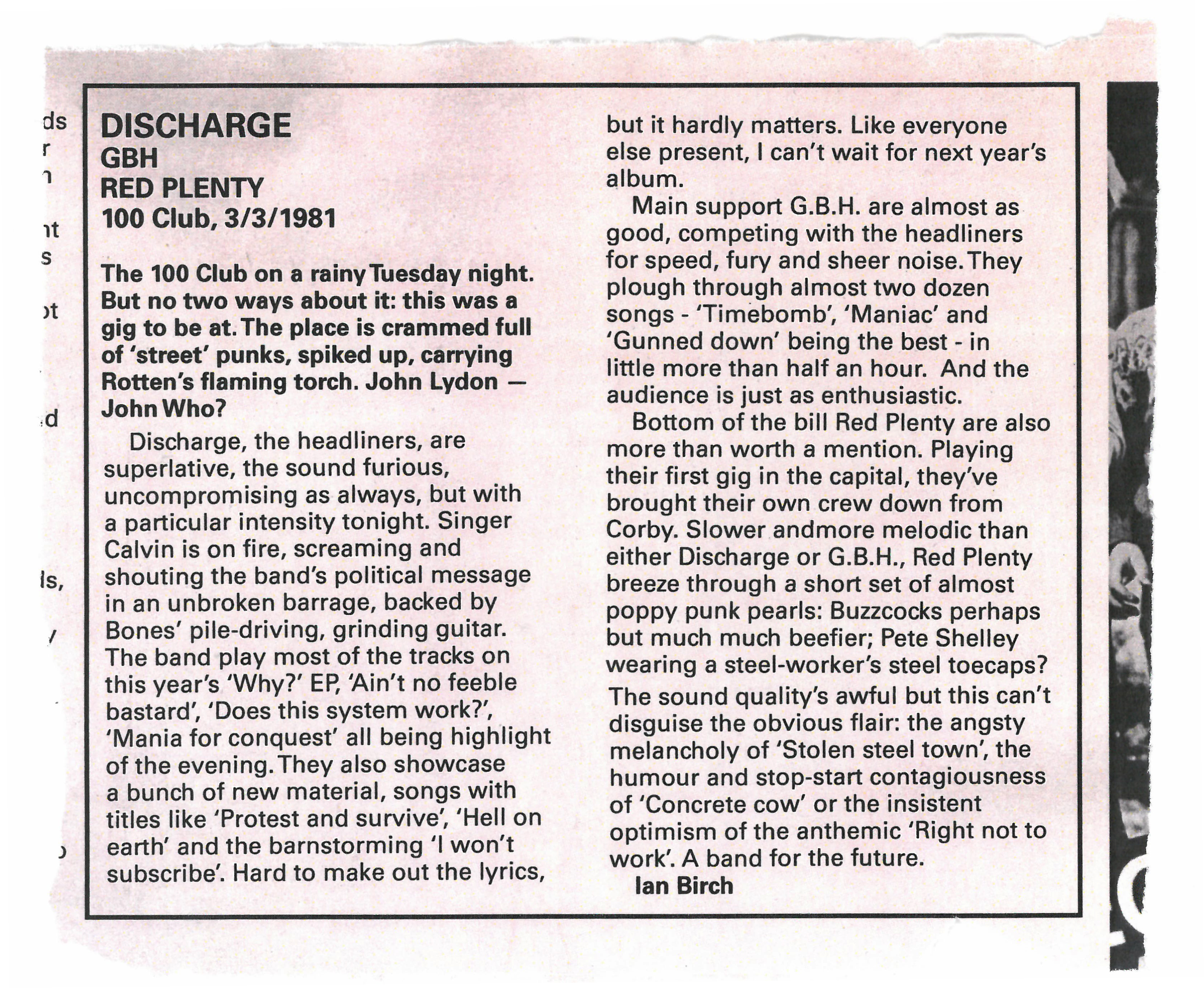

The label ‘Futurist Oi!’ might put you in mind of something daringly experimental – like Cabaret Voltaire on speed? – but there’s nothing challenging about Red Plenty. At a time when bands like the Mekons, PIL or the Pop Group were transforming our idea of what music could do, ‘Right Not To Work’ is straight-up, formulaic guitar-bass-drums stuff: ‘street punk’ as Suzy Perry called it in the NME at the time. The lyrics are equally pedestrian: “Trouble in the factory / Trouble in the mill / Machines are taking over / We got nowhere to go…” At times they make Crass sound like a nuanced exercise in dialectics.

So why the fuss? At the start of the 1980s every school in the UK probably had half a dozen bands who sounded exactly like Red Plenty. Was Zizek Stardust just being wilfully obscure, name-dropping the most arcane bands she could think of?

Then we came across a March 1981 gig review in Melody Maker which called Red Plenty “a band for the future”. It’s a throwaway line but it set us thinking about what sort of future this band from the past might represent. Viv Albertine also touched on it in her brilliant memoir, Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys, where she talks about Red Plenty trying to “escape” the monotony of New Town life.

Like other New Towns, Corby seemed to embody the values of modernity, social progress and cosmopolitanism in the booming 1960s. But all that changed when British Steel announced plans to close the steelworks with an estimated loss of 10,000 jobs. Overnight Corby became a byword for Thatcherism and a taste of what was to come for the rest of the working class. There was anger, hurt, and protest: the town was at the centre of the 1980 national steel strike. But Thatcher refused to intervene and in the following years unemployment in the town reached 30%, bringing a whole slew of social problems which still linger today (it’s regularly listed in the top ten of worst towns to live in).

So that’s the context out which Red Plenty emerged. Steel closures, job losses, an aggressive Tory government… It all sounds eerily familiar, and perhaps that helps to explain the resonance in 2015.

But there’s more. While the left were marching to save jobs, Red Plenty were singing about the right not to work. While union leaders were denouncing a heartless government for throwing people “on the scrapheap”, Red Plenty were confidently celebrating a life against work. On ‘Five Year Plan’ they chant “Five year plan / Five year plan / We don’t want to work / Let the robots do it” (bizarrely it was a cry that seems to have been taken up at Corby Town FC matches, presumably by Red Plenty and their mates). When you set that against recent books by the likes of Paul Mason, Nick Dyer-Witheford, and Nick Srnicek & Alex Williams, Red Plenty begin to appear utterly contemporary.

But there’s more. While the left were marching to save jobs, Red Plenty were singing about the right not to work. While union leaders were denouncing a heartless government for throwing people “on the scrapheap”, Red Plenty were confidently celebrating a life against work. On ‘Five Year Plan’ they chant “Five year plan / Five year plan / We don’t want to work / Let the robots do it” (bizarrely it was a cry that seems to have been taken up at Corby Town FC matches, presumably by Red Plenty and their mates). When you set that against recent books by the likes of Paul Mason, Nick Dyer-Witheford, and Nick Srnicek & Alex Williams, Red Plenty begin to appear utterly contemporary.

Rediscovering Red Plenty isn’t (just) about revealing a hidden history, the explosive promise of the post-punk era. It’s about the way Red Plenty reveal the promise of a different timeline, another history we could have lived through. At certain points, the possibilities of a non-capitalist life become blindingly obvious to a lot of people at the same time. Our horizons shift. As mass unemployment started to bite in the early 1980s, it felt like there was another, better world just out of reach. Thirty five years later, there’s something similar hanging in the air.

Maybe the lesson we learn from the story of Red Plenty is a very simple one: sometimes you have to go back before you can go forward.

2 Comments