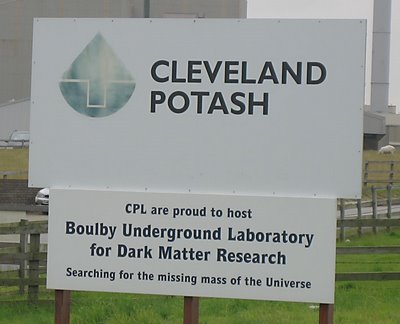

I know I’m a bit late with this (I’ve been searching for the missing mass of the universe) but I stumbled across an interesting snippet about the response to Tony Wilson’s death. Apparently someone went down to Whitworth Street and chucked a load of yellow and black paint over the posh flats where the Hacienda used to stand. OK, it’s not big, and it’s not clever but it makes a lot more sense than some of the shite that I’ve come across.

As ever it’s more interesting to pan out a little and look at the wider context. Here’s something we wrote last year:

Let’s look at the refrain of the ‘entrepreneur’. For the left this is a dirty word, and with good reason: it conjures up images of Richard Branson, of creativity channelled into money-making. But it also contains a certain dynamism, an air of initiative, in fact an imaginary of a kind of activist attitude to life. Indeed we might be putting on free parties, gigs, or film showings, rather than launching perfumes, but we still act in ways somewhat similar to entrepreneurs: we organise events and try to focus social cooperation and attention on certain points. We’re always looking for areas where innovation might arise. The DIY culture of punk is a great example of how a moment of excess caused a massive explosion of creativity and social wealth. There is a difference in perspective though. A capitalist entrepreneur is looking for potential moments of excess in order to enclose it, to privatise it, and ultimately feed off it. Our angle is to keep it open, in order to let others in, and to find out how it might resonate with others and hurl us into other worlds and ways of being.

Seems a pretty accurate description of Tony Wilson. He was never too bothered about being correct; he was interested in making things happen. Or rather, he was interested in making conditions for the creation of new truths. In that sense he didn’t exist outside of his context (and over the last few years his pronouncements had started to sound more and more twattish – independence for the North West!?! – precisely because they weren’t resonating in the same way they once had). And I think there might be a connection here to ideas we’ve been tossing about on affinity and identity.

Crudely put, identity politics tends to operate on the basis of changing a world, which is ‘out there’, without any impact on ourselves. It suggests that battles are lost and won by shuffling pieces on a chess board: ‘OK, we need to link up with organised workers here, build a coalition with feminists from the global South here, and then maybe move in a gay and lesbian battalion here. But that still leaves our left flank exposed to counter-attack by native struggles here…’

From this perspective, Tony Wilson was a pain in the arse, a loose cannon, someone who got up everyone’s nose. But if we think about affinity, then there’s a little more method in his madness. It’s less about ideology or fixed categories, and more about shared affect. People moving together. Of course it’s messy and inchoate (this is dark matter, and dark energy after all), and for every ‘success’ there are a dozen fuck-ups. But each success itself only creates further openings, further problematics. So it goes… This is how it was with punk. Which is why the least interesting thing about punk was the squabbles between ‘first’ and ‘second’ generation punks: once punk hit the headlines, any attempt to restrict it to those in the know was doomed to failure. The tension between punk-as-hip-minority and punk-as-mass-movement was just that, a tension rather than a divide. There was the same tension in the Madchester scene, with the usual scramble to claim authenticity. And it also relates to the tension between audience and public. The audience are the paying punters, but at some stages they can become the public who are inextricably part of the performance. Think Woodstock or Spike Island…

Once the public/audience/performer thing breaks down, who knows what can happen… I’ve just finished reading a book which tries to link today’s globalisation struggles to the working class battles which raged over the past two centuries. It’s more micro-level reportage than analysis, but I came across two fantastic passages which are worth noting.The first relates to the wave of factory occupations in France in 1936 (emphasis added):

Contagion, imitation, certainly played a decisive role in a large number of cases. The very novelty of the undertaking was a source of attraction – with its creation of a whole new set of situations – the feeling of escape from the routine of everyday life, the breaking down of the barrier between private lives and the world of work, the transformation of the workplace into a place of residence, fulfilment of the desire for action, of the need to ‘do something’ at a time when everyone felt that important changes were coming. All these elements played a part in the spread of the occupations and helped to account for participants’ universal enthusiasm and cheerfulness.

And here’s an account of the end of a sit-in in Flint, Michigan in 1937:

As the exhilaration of our first union victory wore off, the gang was occupied with thoughts of leaving the silent factory… One found himself wondering what home life would be like again. Nothing that happened before the strike began seemed to register in the mind any more. It is as if time itself started with this strike. What will it be like to go home and to come back tomorrow with motors running and the long-silenced machines roaring again? But that is for the future… Now the door is opening.

Open with Tony Wilson. Close with factory. Exit stage left.

1 Comment