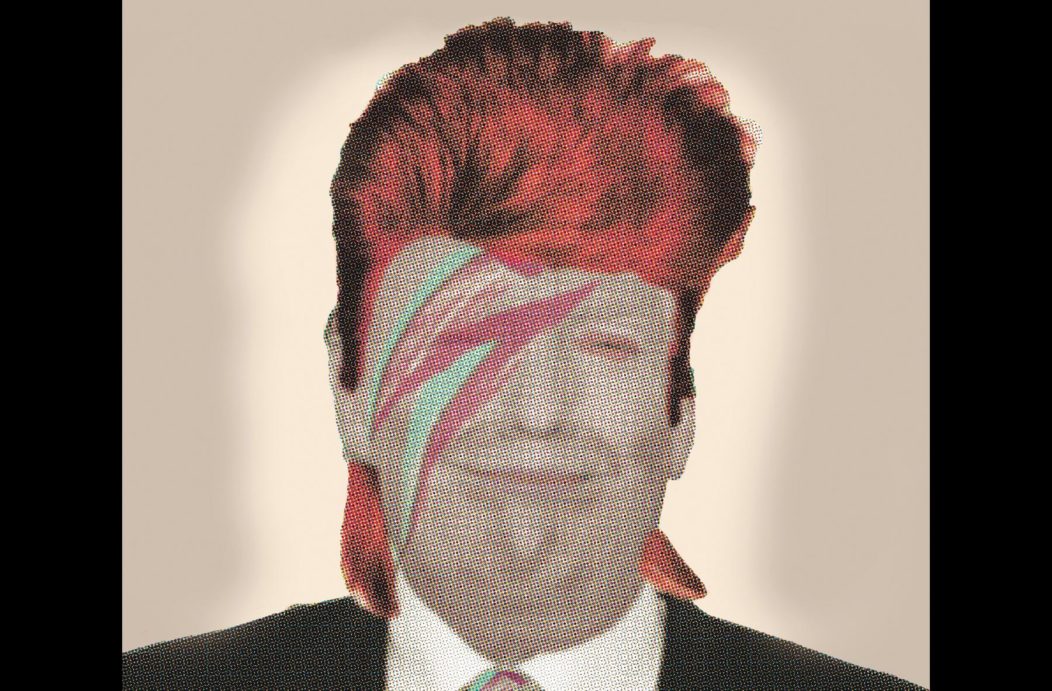

The music writer Simon Reynolds has a new book out, Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and its legacy, from the Seventies to the Twenty-First Century. To coincide with its publication, he wrote an article in the Guardian with the headline, Is Politics the New Glam Rock? Funnily enough my fellow Free Association writers and I wrote our own article a few years back, proposing Ziggy Stardust as a potential model for the kind of political leader that could fit into a libertarian socialist politics. Despite starting from a similar move, thinking political leadership through the terms of Glam Rock, Reynolds’s conclusion couldn’t be more different. He holds Donald Trump up as his example of a politician in the Glam Rock style and that’s certainly not what we had in mind. Of course, pop culture is ambiguous and contradictory by nature, that goes doubly so for Glam, still it’s interesting that those ambiguities can be worked out in such different directions.

There’s three parts to Reynolds’s case for Trump as Glam stomper. He begins by arguing:

Trump’s appeal is generally seen in terms of his doom-laden imagery of a weakened, rudderless America. But there is something else going on too: an admiring projection towards a swaggering figure who revels in his wealth, free to do and say whatever he wants. Trump is an aspirational figure as much as a mouthpiece for resentment and rancour.

This idea of projection is vital in understanding the relationship between fan and icon, or follower and leader. It describes the way icons act as screens upon which fans project their own desires. The most successful icons come to stand in for particular social fantasies, which can tell us much about contemporary society. So what fantasy does Trump represent? I think its the fantasy of a sociopathic version of freedom.

Adam Kotsko argues, in his book Why Do We Love Sociopaths?, that the overwhelming popularity of sociopaths in contemporary TV, from Tony Soprano to Jack Bauer to contestants on The Apprentice, reveals an obscured social fantasy of what it would means to be free. The hypothesis is:

that the sociopaths we watch on TV allow us to indulge in a kind of thought experiment, based on the question: ‘what if I really and truly did not give a fuck about anyone?’ And the answer they provide? ‘Then I would be powerful and free.’

Doesn’t this reflect part of Trump’s attraction for many Americans? His lack of human empathy, backed up by his money, frees him from the rules and bounds of human decency within which the rest of us are trapped.

If Trump represents a sociopathic aspiration, then it’s his glitzy vulgarity that links him to Glam. To this Reynolds adds a secondary charge of shared megalomania.

Trump and the glam rockers share an obsession with fame and a ruthless drive to conquer and devour the world’s attention. Trump actually plays “We Are the Champions” by Queen (a band aligned with glam in its early days) at his rallies, because its triumphalist refrain – ‘no time for losers’ – crystallises his economic Darwinist worldview.

While all icons and leaders want attention some want it in order to further a cause. Trump and the Glam Rockers are accused of wanting attention for attention’s sake. Which leads us to the final characteristic with which Reynolds ties Trump to Glam, his inconsistency.

Bowie conjured up new personas to stay one step ahead of pop’s fickle fluctuations and keep himself creatively stimulated. With no fixed political principles, Trump’s only consistency is salesmanship and showmanship: the ability to stage his public life as a drama.

Of course, the ambiguous play between authenticity and artifice is central to the attraction of pop culture and Glam Rock pushes this to the extreme. But it’s here that Reynolds undercooks his analysis in the Guardian article. He has to play down Glam’s artifice in order to link it to Trump. In Shock and Awe, on the other hand, he goes much further and reveals aspects of Glam that lead away from a Glam Rock Trump.

Glam rock drew attention to itself as fake. Glam performers were despotic, dominating the audience (as all true showbiz entertainers do). But the also engaged in a kind of mocking self-deconstruction of their own personae and poses, sending up the absurdity of performance… Glam idols… espoused the notion that the figure who appeared onstage or on record wasn’t a real person but a constructed persona, one that didn’t necessarily have any correlation with a performer’s actual self or how they were in everyday life.

Trump’s inconsistency is lazy and insouciant; it’s very different to Glam Rock reinvention. I get no sense that there’s a real, more nuanced Trump hiding beneath the mask. He is Trump all the way down; an empty vessel built of immaturity and insecurity all packaged up with a sociopathic sheen. Such emptiness can actually be an asset for an icon, making it less likely that people’s projected desires will be contradicted.

By contrast, Reynolds holds up Jeremy Corbyn as, “the real anti-glam leader of our age… viscerally opposed to – and fundamentally incapable of – political theatre”. Corbyn’s shtick is sincerity. As Gary Young perceptively argues, Corbyn’s supporters don’t come to his rallies “to be entertained” but “to have a basic sense of decency reflected back to them through their politics.” It’s an approach that builds on the Left’s desire to be seen as decent and honest but in some ways it plays into the prejudices of the seething mass of ressentiments coursing through British society. I worry that Corbyn represents the fantasy of historical consolation, his decency says ‘we may lose in the here and now but history will prove us right in the end.’

Another strategy presents itself when we look at how Reynolds positions Glam Rock historically in Shock and Awe. He sees it as a transitionary moment in the move away from a countercultural structure of feeling. “Abrasive honesty and an appeal to ‘reality’ and the ‘natural’ were the most formidable weapons in the counterculture armoury”, says Reynolds. Glam is cast as a reactionary move that emerges when that armoury becomes exhausted. “It was a retreat from the political and collective hopes of the sixties into a fantasy trip of individualised escape through stardom.”

Our own position is very different. We live in a world in which individualised escapism is firmly in the driving seat, celebrity is routine and banal, and the idea of a counterculture seems impossibly remote. But at the same time the coordinates of change are flickering back into life. In many countries young people are shifting Left, while active social movements are animating some of the stars of pop and sport; Beyonce’s performance at Superbowl 50, for instance, or Colin Kaepernick’s refusal to stand for the national anthem. In these circumstance perhaps Glam could act once again as a model for a transitional moment but this time in the opposite direction, helping us move from individualised escapism to collective engagement.

That would be a strategy of pushing through Glam rather than withdrawing from it. Embracing the openly constructed nature of Glam icons, with their “mocking self-deconstruction of their own personae and poses” to create the kind of radically de-mystifying model of a political leader we suggested in Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide.

It was precisely the explicit otherworldly inauthenticity of Ziggy Stardust – a supposed emissary through which alien visitors were speaking – that made him such an effective transferential figure. Whereas [Johnny] Rotten’s persona could be mistaken for the actual person of John Lydon, this was less the case with Ziggy. Yet many wanted to adopt the persona because it showed them a way forward: they used it to change themselves and to recognise others who were doing the same. Moreover, it was the suicide of the character, with Bowie killing it off and adopting a new one, which forced the audience to recognise the mechanism of transference. Unlike the final Sex Pistols gig, this transformation didn’t treat the fans as imbecilic subjects of a swindle. Instead it revealed Ziggy Stardust as a shared contrivance through which both star and audience were transforming themselves. Of course even this is not enough for us. The trick is to do away with the star while retaining the character.

It’s unclear what this strategy would look like practice. Perhaps we could start by reconceptualising our figureheads as comets rather than stars, after all they don’t generate their own illumination but are brought into visibility by the active social forces moving through them. To go further we could draw on our long history of collective pseudonyms, such as Captain Swing and Ned Ludd, who became points of unity despite being enacted by different individuals. Then there are the multi-user names experimented with in the 1980s and 1990s, of which Luther Blissett is the most famous. This in turn led to the invention of San Precario, the patron saint of precarious workers, a figurehead for the common condition of workers who don’t share a common workplace. In a similar vein we find the precarious superheroes who hoped to spark a kind of psychic defence by pointing out where the really heroic endeavours are to be found in contemporary society. We might even find it in pop music, with the rebirth of past icons within the problems of the present, or even the future. Which ever way it works out Glam Rock Socialism needs icons that counteract the sociopathic myth that we don’t need other people. They need to be icons that undo themselves, revealing the charisma of collective intelligence beneath the myth of individual genius.

It’s unclear what this strategy would look like practice. Perhaps we could start by reconceptualising our figureheads as comets rather than stars, after all they don’t generate their own illumination but are brought into visibility by the active social forces moving through them. To go further we could draw on our long history of collective pseudonyms, such as Captain Swing and Ned Ludd, who became points of unity despite being enacted by different individuals. Then there are the multi-user names experimented with in the 1980s and 1990s, of which Luther Blissett is the most famous. This in turn led to the invention of San Precario, the patron saint of precarious workers, a figurehead for the common condition of workers who don’t share a common workplace. In a similar vein we find the precarious superheroes who hoped to spark a kind of psychic defence by pointing out where the really heroic endeavours are to be found in contemporary society. We might even find it in pop music, with the rebirth of past icons within the problems of the present, or even the future. Which ever way it works out Glam Rock Socialism needs icons that counteract the sociopathic myth that we don’t need other people. They need to be icons that undo themselves, revealing the charisma of collective intelligence beneath the myth of individual genius.