We gave a talk recently over in Hebden Bridge. What follows are the bare bones of what we said, but if you scroll right to the end, there’s a concrete idea building on a recent post here.

We got asked to talk on the theme “Who will save us from the future?” which is the theme of the latest issue of Turbulence. We’re sort of going to do that but we’re departing a little from what is on the flyer and advertising for this meeting.

The reason for that is that the last few weeks have really emphasised that we’re in the midst of a crisis, and just how large this crisis is and how it could potentially play out into quite significant changes in society. So it seems a bit ludicrous not to talk about this.

We want to still have the original questions in the background, which is sort of who are the agents of change, what connections, conflicts and resonances might there be between the radical Left and radical Greens or perhaps the autonomous left. Which seems to reflect the make-up of this group. Anyway we’re still going to have these questions in the background but we want to address them in terms of the crisis.

Our focus isn’t going to be so much on trying to predict how events will go. That’s a pretty difficult thing to do when you’re in the midst of a crisis. In fact our focus isn’t so much on analysing the crisis in some objective way, but on us – most broadly that means the working class, but more directly us in this room and the networks we’re involved with. We want to focus on how we fit into the crisis, how it affects us. And how it affects the way we struggle, how it might open new possibilities.

We sense an opening: there seems to be change in the offing but no-one can be sure where things are going… We’re not going to say that this is the end of capitalism or anything like that. Capitalism operates through crisis: it works by breaking down. But crises of the magnitude of the one we’re experiencing now tend to lead to big changes in the way capitalism works. It’s quite likely that over the next few years a new regime of regulation will emerge.

In her recent book “The Shock Doctrine” Naomi Klein quotes the neo-liberal guru Milton Friedman: “Only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable.”

This also applies to us to some degree: times of instability are the best times to intervene into a system. What we’d like to do is to discuss how we can intervene with you. We’re not going to talk for long, because we haven’t got any answers but we’ll try and stimulate some discussion.

We face at least four overlapping crises:

1. Credit

2. Food

3. Energy

4. Climate changeWe can look at all these through the lens of RISK, as composed differently i.e. privatised risk or collective risk

1. CREDIT

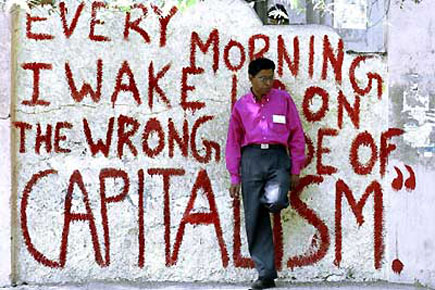

Capitalism is a socialising force: even in its simplest form, it brings people off the land and sets them to work together. But there’s a tendency in the opposite direction too: that of breaking people up (to undermine the power of socialised labour). So we get divisions, hierarchies, separation, compartmentalisation etc. The ideology of liberalism and ‘the individual’ are important here, but so too is the notion of ‘privatisation’. It’s a wooden word now because we take it to mean the break-up and sale of state-managed concerns, but it has a wider sense – the process whereby things that are social or common are forcibly made private.This ‘becoming private’ has assumed greater significance under neoliberalism. We produce our lives in common but one of the main aims of the neoliberal project is to fracture any social arrangement that allows people to maintain common resources for the common good. It does this by smashing them, criminalising them, or simply forcing them to the marketplace.

In the global south this enclosure means the expansion of sweatshops, driving people off land, and the manipulation of environmental catastrophes etc to enforce capitalist discipline. The ‘old’ enclosures, although they’re ongoing all the time. But in the global north neoliberalism has also involved the privatisation of risk in more subtle ways. So risks that used to be socialised through welfare provision, national insurance, etc, are now privatised. Pension provision is one really obvious example, but it goes on everywhere. It runs from the contraction of social housing right through to more ‘trivial’ areas like the extension of ‘choice’ in education: one of my kids is in Year 6, so recently I’ve been spending time visiting high schools, examining prospectuses, checking out bus routes etc. There’s a real pressure on parents here: we are obliged to make the ‘right’ choices for our kids so as to maximise their future life-chances. We’re also encouraged to make ridiculous projections about their possible ‘careers’.

Now the net result of all this privatisation (this ‘becoming private’) is that it involves us all in the financial markets and puts us far more at risk to market fluctuations and collapse. That means we face an incredible amount of extra risk.

If we look at the current crisis, it represents a collapse of credit. And this is significant because the ‘boom’ of the last 15 years in the UK has been credit-led. Here’s a startling statistic: 97% of money in circulation in UK is debt. We know that the rate of profit has increased massively since 1979, while real wages have been in decline – not least because of the squeeze on the social wage. So this ‘boom’ has been consumer-led boom and has has only been possible by increase in personal indebtedness. UK has the highest level in the world.

There’s a link here to wider politics of neoliberalism, i.e. Thatcherism in UK,

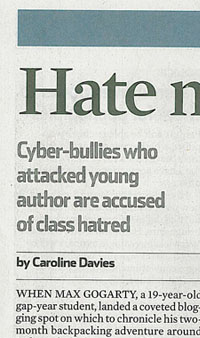

The defeat of the miners’ strike (and the printers etc etc) represented a defeat of collectivity. This is what Thatcher meant when she said: “There is no such thing as society.” Collective action disappeared, it couldn’t find a voice, it couldn’t register. Because of course credit is individual: you buy ‘your own’ house, you have ‘your own’ pension, you sort out ‘your own’ education. In the past wage demands and wage bargaining at least had the merit of being collective. Now we enter the market, naked, as individuals.Finally, this level of personal risk also complicates lines of antagonism, e.g. our pensions are tied to the exploitation of others. “I can only get ahead at expense of others.” It appears to be a zero-sum game which just amplifies the war of all-against-all.

2. FOOD

On a daily level, we could talk about the rising price of food in shops. But let’s also leap to macro-level: millions on verge of starvation. Between May 2007–May 2008 corn prices increased by 46%, wheat prices up 80%, soybeans up 72%, rice up 75% etc etc. This is a crisis on a huge scale. This year food riots have occurred in big cities in 37 countries.Commodity prices have fallen a little since their high point but the real question we should be asking is how has this been made possible. The price hikes are the end result of whole series of policies imposed since 1980s. The World Bank & IMF have imposed Structural Adjustment Programs on developing countries, which involved privatising agricultural lands and commodifying food production and distribution. Agricultural production had to be orientated towards the needs of the global market rather than local needs, resulting in a huge increase in cash crops. There’s been the destruction of subsistence farming, with those thrown off the land being forced into the growing shanty towns and mega slums. Importantly the SAPs also insisted on the dismantling of national food reserves and putting those reserves onto world market.

Countries that were self-sufficent are now net food importers and millions of people are forced to rely on the vagaries of the global grain markets. It’s this reliance that makes global famine possible. So it’s clearly similar to the credit crisis: people are forced onto the market, collective provision is destroyed, the common is enclosed.

This is how neoliberal mechanism work. There’s not less food. Our access to it goes through the market: people starve because they can’t afford food. The risk of starvation is personalised. There’s another link back to credit crisis: sub-prime crisis means houses are re-possessed and then knocked down or sit empty…

3. ENERGY

We could look at the energy crisis in terms of peak oil. That’s the normal framework. But aside from the endless arguments about whether or not we have reached it (never mind what ‘it’ means), it doesn’t seem particularly helpful. Much of the argument seems irrelevant because it’s based on an extrapolation from our current ‘needs’: who knows what we will ‘need’ in years to come?It’s more interesting to look back to the last big energy crisis – the oil shock of the 1970s. This was actually the first edge of the neoliberal counter-offensive to roll back the gains we had made in the 1960s and early 1970s. That crisis was used to break the back of the most powerful working class organisations (not least those in the energy industry, like the miners). The aim of capital’s counter-attack was to drive home the message that prosperity is not guaranteed. Again we see the return of risk to our front doors.

More recently, it’s easy to think of ways consumption patterns have impacted on energy use. The credit-led consumer boom has been totally bound up with the globalisation of markets, the massive rise in container shipping around the world etc. There’s also an interweaving of several different processes: the ideology of car ownership fits with the search for individual solutions to transport fits with a road-building programme fits with the privatisation of public transport and the closure of non-profitable routes etc.

We can also think about this at the level of production. So companies externalise risk wherever possible by sub-contracting and outsourcing production. If you need widgets, you buy them from a supplier rather than make them on site. And you don’t even hold a stock of them: you get what you want when you want. One of the immediate practical consequences of this Just In Time approach is the huge rise of wagons thundering across the road.

Finally we also need to think about the ways in which fossil fuels have historically replaced our energy. Capitalism’s addiction to fossil fuels isn’t an accident. As workers have resisted enclosure of common, and resisted the imposition of work, capitalism has turned to ‘natural resources’ for energy provision.

4. CLIMATE

And sitting over all of these crisis sits the climate change crisis.It overlays other three, but is of a different order and so it’s harder to think through how it links up to the others. Weirdly it’s both the most abstract yet the most real/physical. Its effects are utterly physical yet it’s abstract because the time scale is longer and involves the projection of future interests. There’s a time lag between cause and effect.

But one way of thinking this through is that global warming involves a huge increase of energy into the climate and a large increase of energy injected into any dynamic system causes instability. There is a massive increase in risk.

Two clear ways of dealing with this

a) The market solution that we’re being offered at the minute are aimed at reducing carbon emissions by pricing the poor out. Business as usual. We will bear the brunt (individually) in a new round of austerity with increased costs of travel, carbon taxes, road pricing etc etc. Risk here is same as COSTBut there’s a vicious circle here: neoliberalism means the best individual response to threat of climate change is to get more money and try to insulate ourselves from the increased risk. This means we have to work harder and longer, which inevitably increases carbon emissions.

b) but there is possibility of another approach, which would mean collectivising risk, and collectivising solutions.

And here we can see the importance of seeing all the crises as linked. For instance the huge credit bailouts that are taking place at the moment mean that there’s less public money available for the huge infrastructural changes that climate change and the energy crisis will require.

One of the dangers of overlapping crises is that risk becomes a generalised condition (it’s always been virtual but will become actual). Debt is a good example: if you owe a small amount, it can act as a disciplining mechanism, restricting your ability to act. But if you start to owe a lot, discipline can break down altogether: “The equity underwriting my debt is now in doubt. Cheap credit gone. We may be on brink of recession. Or even complete meltdown. So I might as well fuck off the lot…” It’s the kung-fu principle: as risk becomes generalised, it ceases to be a weapon against us, and potentially becomes a new form of commonality, new ground of struggle.

So to end, we want to look at some struggles that have tried to come to terms with the changes in work and its effects on struggle. Some interesting innovations have happened in struggles against precarity in continental Europe, responding to the lack of the mass workplace as a site of collectivity.

One of these is the Mayday parades, which take the form of carnivals and are modelled more on Gay Pride parades and the love parades that happen in Berlin. They started off in Milan in 2001 with 5,000 people and grew to 50,000 by 2003. These then turned into Euromayday with simultaneous parades in different cities. So in 2006 there were 300,000 participants in 20 cities.

Another interesting innovation is San Precario, the patron saint of the precarious. He was invented as a symbol or icon that all the different experiences could invest their desires in. They make big models of San Precario and carry them round, like the saints parades in Catholic countries. This is an attempt to form a collectivity out of very varied experiences of precarity.

‘Precarity’ is a fancy-sounding word, but it just means a condition of existence without predictability or security. Precarity has never really caught on in this country, as an idea or tool. We’re at a different stage of neo-liberalism than Spain, France or Italy, for example, where it has taken off as a category of struggle. For us, in the UK, precarity isn’t a new condition and we understood it differently as casualisation. However if we experience a more generalised increase in precariousness then some of those tactics might begin resonate.

And in the face of these four overlapping crises, we can also start to think of precarity in a wider sense: it’s not just about work, it’s about existence. Here we can look at the anti-CPE struggles in France in spring 2006, or the actions of the piqueteros in Argentina (they had no workplace so they picketed the cities, throwing up barricades and bringing everything to a halt until their demands were met). And we can also look at innovations in struggles around money and debt: in the UK we have the experience of the Poll Tax revolt to draw on. But there are options: In gReece there have been raids on supermarkets by Robin Hood-type figures, filling trolleys and dumping them outside for people to help themselves. There’s even been talk of a ‘mortgage strike’ here in the UK (and who knows what that would look like).

There are no guarantees here. No-one can know how these crises will play out. But the example of the Argentinazo in December 2001 should remind us how quickly everything can change. There, the struggles of piqueteros etc laid ground for social revolt. They provided the ideas that were laying around. Here we need innovation and experimentation to see what resonates.

So the idea of a Fair Price campaign makes sense, not as a stunt but as a genuine campaign that tries to link up all the crises. It could be linked to the logic of “No profiteering from a crisis” and the logic that exceptional times call for exceptional measures. I think that logic runs like this:

– The government and big business say these are exceptional times. They’ve made exceptions to normal rules and laws, they just suspended competition laws to let Lloyds buy HBOS. At the same time we, ordinary people, have had to put our hands in our pockets and bail out the richest people in the country. They get to keep all of their profits but we have to pay for all of their losses. Well, if it’s exceptional times for them it should be exceptional times for us.

– At the same time as we’re being asked to pay to bail out the banks, food prices are rocketing and – guess what – the supermarkets’ profits have been rocketing too. The supermarkets are cashing in on this crisis, they are acting like spivs, profiteering from hardship.

– No-one believes the government is going to help us out so we should help each other.

So the plan could be as simple as this. Let’s meet outside Tesco’s, discuss together what’s a fair price and then ask to meet the manager and ask him if he’ll reduce prices. The advertised price of goods under UK law is only an offer – it’s called an ‘invitation to treat’. So it is legal to negotiate and managers of stores have some leeway on prices. This is legal, possible and fair.

Again it could be promoted really simply: “Come to Tescos carpark 10am Saturday 10th of blah, blah. Look for the Fair Price banner and join in the discussion. Exceptional times call for exceptional measures! A bailout for them, reductions for us!”

There would have to be a big build-up for this, with letters in local newspapers, posters, etc. It could only work if it was something of a national talking point before the actions. This means campaigning and trying to cause awareness in different ways. But the logic of this makes sense and could reach outside the usual circle of committed activists (i.e. be more than a little Situ stunt). This crisis is going to be continuing for a long time – in fact this might work better in a couple of months when the effects are biting home on main street, as the Americans would say.

Some research would have to be done, e.g. work out what percentage of the price of goods is profit, on average. Also supermarket owners can ask anyone they want to leave their property so we’d need to find a bit of highly visible, adjoining public land or land owned by someone else who isn’t going to be there.