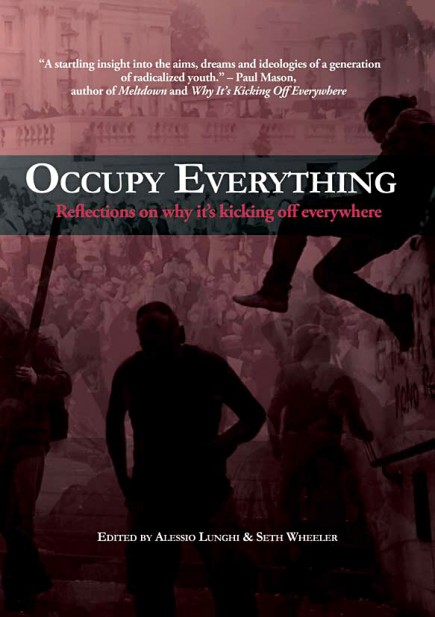

This is the text of a talk I gave at The Space at the Leeds launch of Occupy Everything, an excellent anthology of writings provoked by Paul Mason’s blog post ‘Twenty reasons why it’s kicking off everywhere’

I’ve talked a lot in the last year about the magic of rupture, the little sprinkle of fairy dust that can turn an event into something explosive. I want to leave that to one side and instead think about the magic of consistency, how things hang together (or not) in the aftermath of that rupture. And I want to start by going back to the roots of Western materialist philosophy… and football.

For the Classic philosophers Epicurus and Lucretius, nothing comes into existence out of nothing, and nothing disappears into nothing. For them, the only two entities are body and void. And this is how they present the universe – bodies raining down in straight lines, never touching, never deviating, through a bottomless void. Pretty grim. Actually Lucretius says, it’s not like that. If it was, nothing would ever exist except bodies and void, and we would be robots with every movement and action determined by unbreakable causal chains. Instead, there is what he calls the clinamen or swerve – a spontaneous tiny change of direction in the course of an atom’s downward fall which makes it lean into another atom.

This swerve is vital. Lucretius says: ‘If it were not for this swerve, everything would fall downwards like raindrops through the abyss of space. No collision would take place and no impact of atom upon atom would be created. Thus nature would never have created anything.’

What has this got do with ‘Occupy Everything’? Well, everything.

That vision of an atomised world, of single bodies falling in straight lines through a bottomless void seems very familiar if you’ve ever been on the Tube or stood in a checkout. But we’re also familiar with the idea of a swerve – a magic moment when bodies come together, when individuals coalesce and become a force. So in football we might say that swerve could be something like the Cruyff turn or a crunching tackle, a moment of brilliance (or brutality) that lifts a crowd to its feet and changes the game. Or it might be the audacity of seizing Tahrir Square or putting a boot through the window at Millbank.

Obviously that swerve is much easier in football where you’ve got a set of rules, a clearly identified opposition and 30,000 people who are already up for the encounter. But we can also think of the ruptures that happened at the end of 2010 and the start of 2011 as swerves, as deviations in our falling bodies. People bumped into other people, new bodies were formed and those movements rippled outwards across the globe.

The promise of moments like Millbank or the Arab Spring is that they generate enough consistency between different social actors that new forms of class power, collectivity and organisation can emerge and then recognise themselves.

But there’s a problem. Bodies come together. They get hot. They get sticky. But then things cool. When that happens, bodies drift apart or go off looking for some other encounter.

So how do you keep very different forms of struggle articulated together? And how do you sustain political organisation across the ebb and flow of distinct protest waves?

There’s no easy answer but I think it has to do with finding some sort of consistency or coherence, one that enables bodies to literally stick around. Reading through ‘Occupy Everything’, there are two clear reasons why this is especially important now.

First, we have to take a long term view of the economic crisis that engulfed the world in 2007–8. Even in simple fiscal terms, we are going to be living through its consequences for at least the next ten years. And politically its impact may be even greater, as austerity becomes the new normal. In fifty years time, people might look back and see Keynesianism and social democracy as temporary blips in the normal, brutal functioning of capitalism. Over the next few years, then, there are bound to be waves of resistance followed by periods of quietism and troughs of defeat. Even now, the joy of Millbank and the Arab Spring seem a long time ago.

And when we take this long term view, we need to think again about the effect of speed on our bodies. During the events covered in this book, it was all about the speed of virtual politics – Facebook, Twitter and the power of the meme. But as George Caffentzis has pointed out, the experiences of the last year have actually shown that speed is not enough for political effect. You need momentum as well. If you remember your physics lessons from school, you’ll know that momentum is mass times velocity, so it can mean a small group travelling very fast – via tweets & BBM etc. But if we’re serious about change, it must also mean a much larger number of people moving at a slower pace. In the Arab Spring, for example, what was decisive in the end was massive numbers of physical bodies in physical spaces. So we can think of consistency as a way of bridging that gap between huge numbers of people and small groups moving fast.

And that brings us on to the second reason why finding consistency is crucial. It’s not just our bodies that are in movement. There are other bodies falling down as well. Any one of those can collide with us and send us spinning off in another direction.

In football, a couple of quick goals from the opposition can make a crowd turn in on itself. What was one body becomes 30,000 squabbling individuals, each with their own agenda.

And here we can think about the weak ties of network politics that are so celebrated in this book and in Paul Mason’s. Those weak ties are great because they make movements very elastic, highly responsive and able to grow exponentially. But without more coherent forms of organisation to back them up, those weak ties can make movements very vulnerable to disruption. For me one of the enduring images of late 2010/early 2011 in the UK was that brilliant photo of a boot going through a Millbank window. But fast forward a few months to the August riots. Those virtual social networks which had been so powerful couldn’t hold together all the shocked metrosexual liberals who suddenly discovered their inner fascist. The aftermath of the riots is summed up in those horrible photos of the ‘Broom Army’ – hundreds of people banging the drum for law and order.

So that’s another aim of consistency or coherence: to find ways to help our bodies deal productively with shocks, ruptures and collisions. One of the worst ways of tackling shock is to try and cope with it in an atomised and individual way. If we can develop some sort of consistency, or stickiness, then we can slow down the intensity, collectivise the experience, and create a space for us to take stock and analyse together. So we could think of forms of organisation as shock absorbers or even crumple zones. And for that, spaces like this, and books like this, are absolutely crucial.

So where does that leave us now? All this talk of long-term strategy, of regroupment, of a down-turn, of resignation seems a bit depressing compared to the excitement of the movements covered in this book. If that’s all we’re left with, maybe we should ask what exactly did we gain from the events of 2011? A few north African governments have fallen, but for most of us here in the UK, aren’t we back in the same state of impasse where we began?

Let me answer that with one of Keir’s favourite stories, another football analogy. Let’s call it Riff no. 9. Back in the early 1990s there was a football manager who was trying to introduce a more patient, continental style of football to English players used to a much more direct, physical game. During a training session the manager asks his attackers to pass and move, and pass and move in the final third of the pitch instead of just lumping the ball into the box as they usually do. So they do this, but after five minutes the centre forward pipes up: “Boss, what was the point of all that running? We’re back in the same positions as we started?” “Ah, yes,” says the manager, “but their defenders aren’t.”

Or as Lucretius might say, “nothing disappears into nothing.” The experience of 2011 is in our bodies. We just have to open up to it and use it.

1 Comment