Fredric Jameson described one of the impasses of postmodern culture as the inability ‘to focus our own present, as though we have become incapable of achieving aesthetic representations of our own current experience.’ The past keeps coming back because the present cannot be remembered.

Mark Fisher: Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures

It’s hard to find traction these days. Just when you think you’ve got a handle on things, they slip out of your grasp or melt away to nothing. So it’s easier to cling to the past. Safer, too. If you want an aesthetic representation of our own current experience, perhaps you can find it in Bake-Off, Brexit or the latest reboot from Hollywood.

The fact that the past keeps coming back seems to be part of the post-modern condition, the sense that the present is somehow broken or inaccessible. As such, it’s inescapably bound up with the logic of advanced capitalism. Neoliberal principles are being relentlessly applied to the field of art and culture, asset-stripping recent history for bite-sized chunks that can be sold back to us. It’s a vicious circle because this then feeds into a cynical (half-assed) subjectivity which is quick to embrace lazy, cut-price nostalgia – like those never-ending “Do you remember Spangles and Spacehoppers?” TV shows. This is culture as comfort-food, an oppressive regurgitation of the same pap masquerading as something different. It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that we’re running on the spot, fiddling while Rome burns.

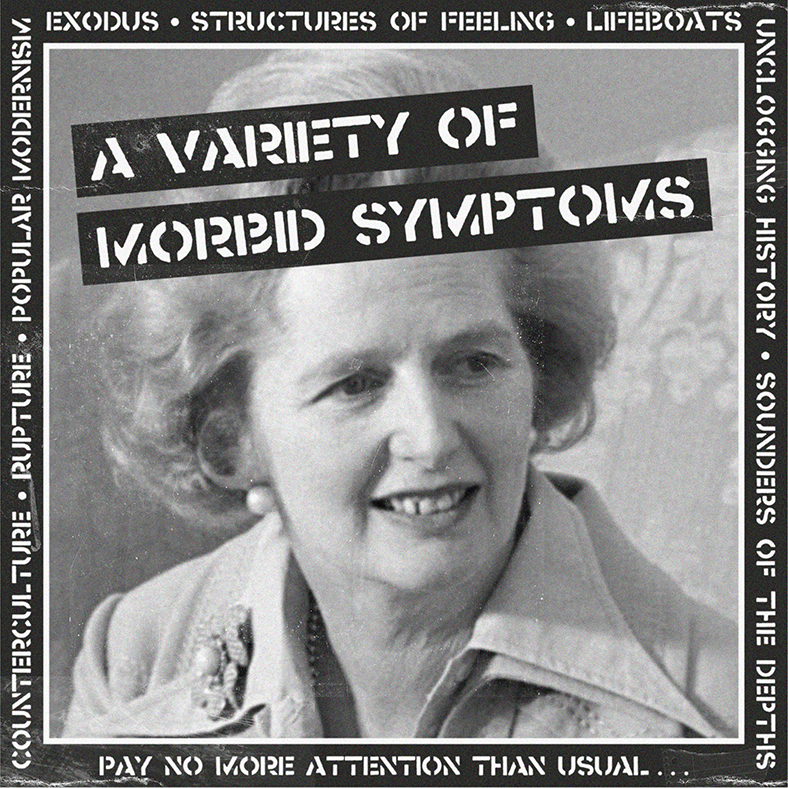

But just as there’s more than one past to excavate, there’s also a different sort of looking back. Sometimes you need to reflect precisely in order to go forward. We’ve been raking over the bones of our own dead – writing about 1980s anarcho-punk for a new collection by Minor Compositions as a way of writing about the political impasse of 2016.

Like punk, anarcho-punk had a conflicted relationship with the past. While it liked to position itself as a rupture, a break with all that had gone before, there was also a clear continuity with many aspects of 1960s counterculture – something which Crass would make explicit later on. In The Kids Was Just Crass we argue that whatever the claims of any pop-cultural revolution, there can be no wiping out of the past, no Year Zero. Instead, “moments of excess open up the future precisely by reconfiguring the past, unclogging history and opening up new lines of continuity”.

Perhaps there are now other lines of continuity to explore. Anarcho-punk emerged some 35 years ago under conditions which seem eerily familiar – a rampant Tory government, a deepening economic depression, a grassroots Labour left under attack from its own party, a groundswell of racism fuelled by fears over immigration, etc – all played out against a backdrop of impending global apocalypse. The word ‘crisis’ loomed large then, just as it does now. Crisis? Yeah, sometimes it feels like we’re always living through a crisis – if not a crisis of the state, then a crisis of the economy, or a crisis of movement. But in the early 1980s it definitely felt like we were living at the fag-end of an era. And in retrospect that’s exactly how it turned out. There’s something similar about 2016, a sense that our world has been interrupted, put on hold.

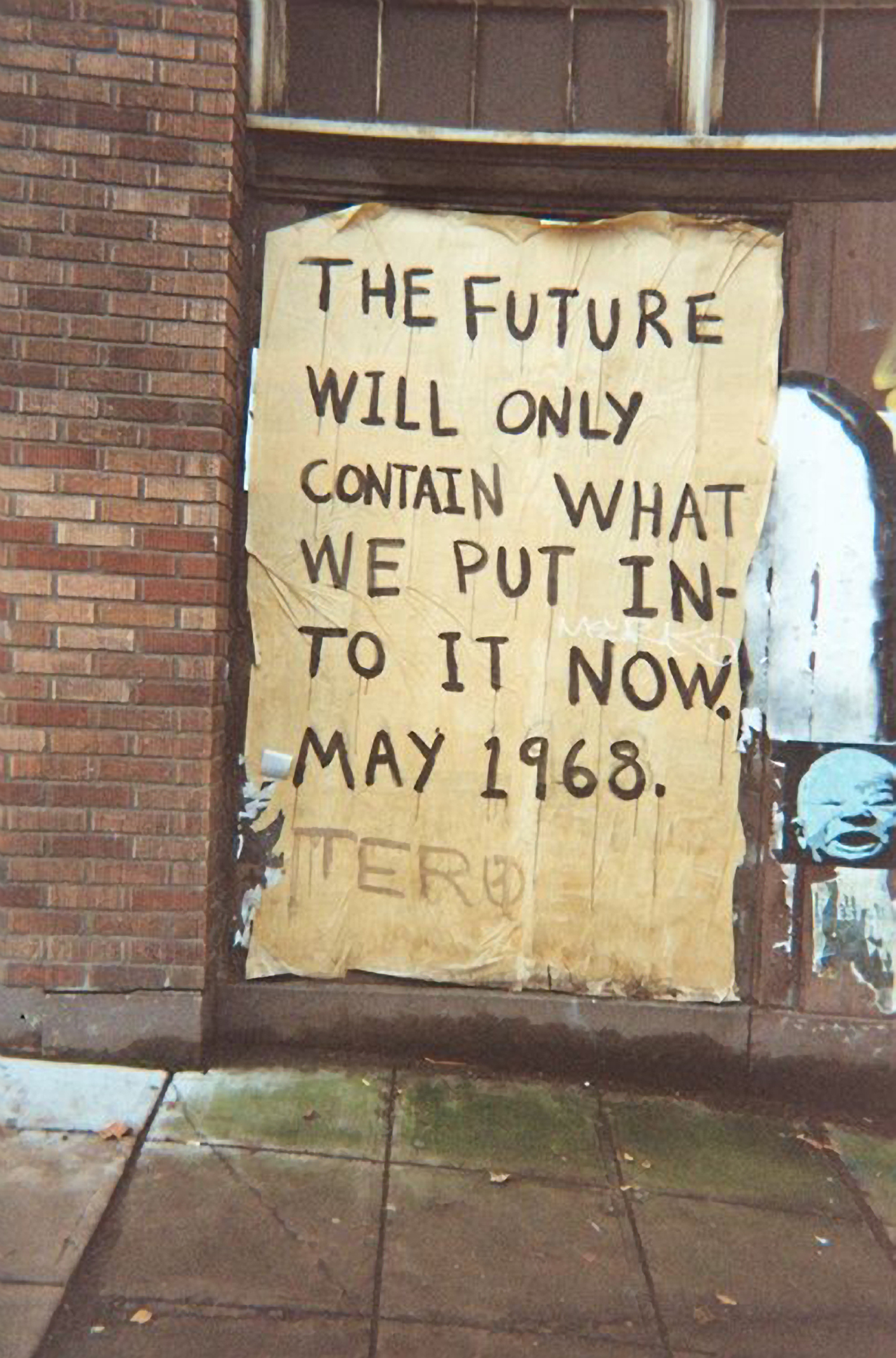

In the years following the defeat of the Paris Commune, Stephane Mallarmé defined the era as inert time, a period when “a present is lacking.” That also seems fitting today: the present cannot be remembered because it barely exists. It’s hardly surprising that the past keeps coming back to haunt us as we try to work out how to step into the future.

Comments Off on The future will only contain what we put into it now