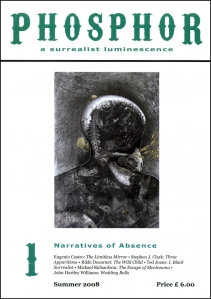

I went to a great evening of talks and films put on by the Leeds Surrealist Group yesterday. They presented material from their new journal Phospher, which includes a positive review of Turbulence 3. There was a load of interesting stuff but the main focus was on surrealism and games, including a talk on the subject by our good friend Gaz. The talk is reproduced below but before we get to that I just want to riff off on the theme a little.

To give you a flavour of what they mean I’ll describe a little of what happened. One of the games the group has played was called Explorations of Absence which involved collective interpretations, of what they called, atopoi or non-places. “The unused or abandoned interspaces between different planned spaces”. The sort of places that children seek out. A photo was taken of such a place and then different reactions to the photographs were made, these then sparked of the collective creation of an object that was left at the non-place. Last night a picture of an over grown path was shown and then people took it in turns reading out their reactions and responses to it. It really worked for me and reminded me of the optical illusion rabbit/duck or two faces/vase pictures. You would look at the path one way and then someone’s interpretation would go up a level of scale and all of a sudden you could only see it as a landscape with trees and alluvial fields of boulders.

Anyway Gaz’s talk really got me excited as he talked about surrealist games as the combination of collectivity and chance and called surrealism the communism of genius. You can read all that for yourselves but I was struck by how that resonates with our own concerns and indeed one of the central concerns of contemporary theory and indeed social movement practice, namely how do we get a politics adequate to the event. We have tried to think this through in terms of moments of excess.

I asked a question about the possibility of the games bursting the bounds of the participants, that is getting out of control. But I suppose what I was really asking was what relation do such games have with wider social transformation. Gaz’s answer was that revolution was the biggest game of all and I suppose we are all looking for a way to get that game started, while making sure everyone else is able to join in.

Surrealist Games

Gareth Brown

Samantha, blithely disregarding even the slightest pretence of playing chess in the usual manner (she was, it is true, only three or four years old), announced that as far as she was concerned, it was vastly more fun to put the pieces into a small wagon and give them wild rides around the yard. This incident strongly affected me at the time. Recalling it now, I am reminded of Andre Breton’s admonition, also regarding chess, that “it is the game that must be changed, not the pieces”

That’s from a bit of writing by Franklin Rosemont called ‘The Only Game in Town’

I’m going to talk to you a bit about surrealist games. Kenneth has already talked about the fact that surrealism isn’t an aesthetic movement or an art movement or anything like that. In fact, the absence of surrealist artefacts (texts, images, objects, etc) would not in any way imply the absence of surrealism since these things are, by and large, simply a means for communicating or for helping to understand, the results or revelations of surrealist games or they’re by-products created by the processes of game playing, the excrement of game playing if you like. And, although surrealist artefacts are constantly created, they are not a vital organ of surrealist activity. Games however, are. If there is one activity that remains absolutely essential to us as surrealists, it’s game playing and certainly this is something that’s glossed over in the popular understanding of surrealism which is very much an understanding derived from that of the gallery owner who of course needs to fill the gallery with artefacts so who can blame them for skewing it in their favour.

In one of his books, (I forget which), Freud talks about a game beloved of children (although I can’t say that I’ve ever seen any children playing it) to which I think he gives the name Fort Da (Fort – ‘Off you go’, Da – ‘Here you are’). It’s a game that involves a bobbin with a piece of string tied around it. The bobbin is allowed to roll off accompanied by an exclamation of the word ‘Fort!’ and then reeled back in accompanied by an exclamation of the word ‘Da!‘ The point of this game is to play with chance (and really with fear) in a way that is totally inconsequential. The bobbin always returns but the fun is derived from the unconscious fear that it might not and relief when it does. This kind of game is in keeping with the ideas of game play developed by Johann Huizinga and Roger Caillois for whom the defining element of a game is that they end in a situation identical to that prevailing at the beginning. This, it seems to me describes one of three totally distinct forms of game. It’s the form that in capitalism gets sectioned off and isolated as leisure or pastime for the two-fold reason that its lack of productivity means that it’s of no use in the work place and of much use in ensuring that nothing transformative ever happens outside of the work place (pastime – to pass the time when not at work). We mustn’t forget, of course, that even though these games are unproductive in themselves, huge markets form around them. It’s not all bobbins and string any more.

The second form of game is the competitive game, which is concerned with the acquisition of individual wealth (I know this category also includes team games but the principle is still the same) and therefore doesn’t fit with this idea of games as inconsequential although it’s only semi-transformative which is why it is still exalted in present day society. The need to compete and to win is important to capital but actually the winners and competitors are of no importance at all. It’s the taking part that counts. In stark contrast with Freud’s Fort Da, It’s also concerned with the domestication or elimination of chance. This is in stark contrast too with the third form of game, a form of which the surrealist game is representative, a form of game that‘s the only form of the three that’s transformative in a way that is potentially subversive. This form of game is concerned not with acquisition but with expenditure.

The Portuguese poet Mario Cesariny once remarked that the whole world is organised on the model of the Exquisite Corpse.

Exquisite Corpse is one of the earliest games developed by surrealists based around the idea that you have a set of players who each write an element of a sentence without being aware of the previous player’s contribution so that you get a sentence like ‘The exquisite corpse drinks the young wine’ (the sentence from which the game gets it’s name) where each adjective, each noun, and the verb are all contributed by different players. I used to play something not dissimilar in school only it was known as ‘consequences’. There are, of course, countless possibilities for variants of this game. Indeed, you will find few coffee-table art books on surrealism that don’t contain at least one example of exquisite corpse played as an image-based game.

The Portuguese poet Mario Cesariny once remarked that the whole world is organised on the model of the Exquisite Corpse.

This is illustrative one of the fundamental positions of surrealism: that the world is created and life is transformed through the interplay of collectivity and chance. (An essentially Marxist position but one that focuses on the aleatory as opposed to the deterministic) and it’s certainly true, whether you’re talking about the natural world or capitalist production. Horizontal, non-hierarchical modes of organising such as that employed by the surrealist movement and in Anarchism simply lay this fact bare but it exists everywhere else as well. That’s why Svejkism (also known as work to rule) is such an effective form of workplace sabotage. Svejk comes from a book by a Czech author Hajek called ‘The Good Soldier Svejk’. He’s basically a soldier who brings about the downfall of the Czech military by following orders to the letter. What this tactic does is pull the reins on all the collective creativity that forms the essential part of any process of production thus exposing the illusion at the heart of capitalism: that the world is created and transformed via a process of competition between corporations and sovereign individuals. This is why surrealist game playing is subversive. It exposes the process vital to the transformation of life.

I said that surrealist games focus on the aleatory, on chance. Really this is an extension on their focus on collectivity. It enables the collectivity to exceed the boundaries of the actual participants themselves, resulting in play that encompasses the weather, the urban landscape, nature, detritus, relationships with other human beings etc, etc and most importantly the marvellous, that which can be found when objective chance throws out unlikely tendrils between objects or ideas or sounds etc. that create moments of disturbing friction that seem to tear big strips out of the functionalist form of reality and jar with time and space in a way that can be extremely arresting. So objective chance, in a sense, is the invisible participant in all surrealist games.

Largely, as is certainly the case with ‘Exquisite Corpse’ they are ways of exploring a collective intelligence, a collective creativity that goes far beyond the sum of its parts. Surrealism has been described as ‘the communism of genius’. The surrealist position is that genius as a thing to be found in a select smattering of golden selves is a scam, a great big charade, with social atomisation and the creation of the specialist at its heart. In fact it is in the in-between spaces that genius is to be found. When Lautreamont said ‘the conditions must exist whereby poetry can be made by all’ I don’t think he meant ‘whereby poetry can be made by each’, I think he was trying to emphasise the same collective intelligence that surrealist games attempt to investigate rather than being a simple, anti-hierarchical gesture about equal rights. (Comte de Lautreamont, real name Isadore Ducasse, is an important influence for surrealists. That quote comes from ‘Les Chants de Maldoror’).

So Kenneth also pointed out that the surrealist movement and surrealist activity is strongly internationalist. Certainly many of the games we play cross national boundaries and it was really in 1968 with a document entitled ‘the platform of Prague’ signed by members of the surrealist groups in Prague and Paris that games became the most important focal point for surrealist activity (although they’d always been important). I’ll just read a little bit from that document.

As regards the sharing of thought, which remains one of our specific pre-occupations, the most lively impetus will be given, in surrealism, to game playing and experimental activities. We place all of our intellectual hopes in both of them. Animating the life of groups, exalting friendship by integrating it with spiritual exchanges, they establish each spirit in a state of intersubjectivity where the facts of the present and individual history resound in a consonant way. Surrealist games are a collective expression of the pleasure principle. They are increasingly necessary since both technocratic oppression and the civilisation of computers do nothing but inexorably increase the weight of the reality principle. Intellectual blood regenerates itself through experimental activity. We appeal constantly to individual initiatives to propose the axis of research for all.

In The Platform of Prague they talk about the importance of experimental activities but I prefer to think of games as exploratory since experimental can carry with it a sort of positivist connotation which is very much at odds with surrealist exploration. Similarly, it’s often said that surrealist games are revelatory (in fact I think I used this word myself earlier) but again this is an idea that for me is problematic or at least it is if this is seen as a function of surrealist games because of course, it’s not really about revealing something that’s already there. Revelation if anything, has even stronger positivist connotations that experimentation. The point of the surrealist game is very much to cut the string and throw the bobbin and see what happens. You may never see it again. You may find the bobbin years later covered in moss and lichen. The bobbin may be carried off in the stomach of a horse or an owl. Most importantly, you don’t know. You have no idea what you’re hoping to find or where it might be. Alternatively it could be to wander round looking for string to pull without knowing what might be on the other end. The point of competitive game playing is the opposite. It is to do what ever you need to do in order to make the bobbin reappear. You know precisely what you are looking for (presumably victory). Precisely where you’re going.

The other main aspect of the surrealist game is as a sort of symbolic exchange between players. This point is clearly very important for the authors of The Platform of Prague. Through games, this sort gift economy develops within the movement, a permanent reciprocity through which bonds are formed and strengthened and collective activity is ensured.

2 Comments