Oh dear, last weeks wide-eyed talk of green shoots have already been replaced by a new sense of gloom and talk of a double dip recession. That must rank amongst the shortest, least noticeable economic recoveries in history. I suppose wishful thinking can only get you so far. Ultimately the pundits and spinners are going to have to face up to the idea that the present economic crisis is not just a normal moment in the usual cycle of boom and bust but is a more fundamental and potentially epochal affair.

Oh dear, last weeks wide-eyed talk of green shoots have already been replaced by a new sense of gloom and talk of a double dip recession. That must rank amongst the shortest, least noticeable economic recoveries in history. I suppose wishful thinking can only get you so far. Ultimately the pundits and spinners are going to have to face up to the idea that the present economic crisis is not just a normal moment in the usual cycle of boom and bust but is a more fundamental and potentially epochal affair.

What do I mean by this? Well the first thing to say is the crisis doesn’t, on its own, mean the end of capitalism, it is, however, an interruption in the general direction in which global society has been pushed over the last thirty years. That is to say it does seem to be a fundamental crisis for the neo-liberal mode of capital accumulation. Central to this assessment is the way the crisis has broken the implicit neo-liberal deal of compensating for stagnant wages through access to cheap debt. We have talked about this deal elsewhere but it was also outlined with surprising accuracy in a recent article in the Financial Times titled: Debt is capitalism’s dirty little secret.

The FT article goes as far as admitting that neo-liberalism is fundamentally about the transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich and argues that cheap debt was the only thing that prevented revolution. This seems like a vindication of David Harvey argument that neo-liberalism is based on ‘accumulation by dispossession’ and of course this process hasn’t ended with the crisis. The bank bailouts are a huge and naked transfer of wealth to the wealthy. Indeed some have argued that the bailouts in the global north are playing the role that Structural Adjustment Programmes have played in the global south. There is a lot of truth to this. The bailouts are a neo-liberal solution to the crisis in neo-liberalism, in this sense they are just neo-liberalism intensified. But it is this degree of intensity that indicates it is more than neo-liberalism in normal operation. After all it’s when a system enters a crisis situation; when it is far from equilibrium, that we can see most clearly the intensive processes that make it up. The socialisation of risk to defend the privatisation of profits follows neo-liberal logic but destroys neo-liberal ideology. It is for this reason that the underlying processes of neo-liberalism have become apparent not just to us but to the Financial Times. Neo-liberalism has been stripped of the fetishisms that would normal disguise it and this has caused a real, ongoing ideological crisis. At the very least there’s been a significant wobble, if not a total collapse, in the religious hokum of the invisible hand of the market magically producing the common good. The ideas and practices that have formed the middle ground of society are ceasing to make sense, even on their own terms.

Of course this raises the question of what happens now?

One common assumption is that when the middle ground of society is in crisis then a new middle ground will have to emerge; a new deal will have to be struck. There is an expectation that some version of Keynesianism must follow, a New, New Deal or perhaps a Green New Deal. There are however several serious obstacles to this scenario, not least amongst them is that the world still has a fundamentally neo-liberal composition. The common sense of society, how we understand the world and ourselves, (within which the political middle ground develops) has been fundamentally transformed by thirty years of neo-liberal governance (although this is true to greater or lesser degree in different parts of the world).

One important point we should recognise is that neo-liberalism has only a limited role for its own ideological argument. Such argument is used to create neo-liberal ideologues and activists but this isn’t how it transforms wider subjectivity or our common sense understandings of what is possible. These changes are brought about more operationally than ideologically. That is to say that neo-liberal common sense is actively brought about by interventions into class composition rather than through ideological argument. Neo-liberalism re-organises material processes, it intervenes into society to try and bring about the social reality that its ideology claims already exists. It actively tries to create its own presuppositions.

Instead of being persuaded by the power of argument, people are trained to view themselves as homo-economicus by being forced to engage in markets. It is in this way that people come to view themselves as human capital; that is as little enterprises locked in competition with others. Indeed this is increasingly true not just in our economic activities but throughout our whole lives. Thus we have the imposition of markets into more and more areas of life, which mean increasingly huge bureaucracies and more and more corruptive systems of measure. This is the Market Stalinism has taken hold in the public services.

Foucault, in his lectures on neo-liberalism, talks about changes in Governmentality, that is the manner or mentality through which people are governed and govern themselves.

Governmentality is multi-scalar; it isn’t just about global governance or how to govern states but also about the management of individuals. It is about how you should live. It sets up a model of life and then establishes mechanisms whereby you are shepherded towards ‘freely’ choosing that manner of living. If you want to participate in society you are force to behave as homo-economicus. The markets are rigged to make certain actions make more sense and other actions less sense. The dice are loaded.

Of course, despite the circularity of its self-fulfilling and self-affirming prophecy, there have always been large areas of life that haven’t accorded with neo-liberalism. However held in place by the neo-liberal deal it has seemed quite stabile for a long time. Access to cheap credit was essential for neo-liberalism to solve the problem of effective demand, to make sense on its own terms and to disguise the huge transfers of wealth and power that were taking place. This manner of living is now in real crisis and many of the things that were previously rigged to make sense, no longer do. A couple of years ago in the UK you were acting irrationally if you rented a house when you could afford to buy, now the reverse is true.

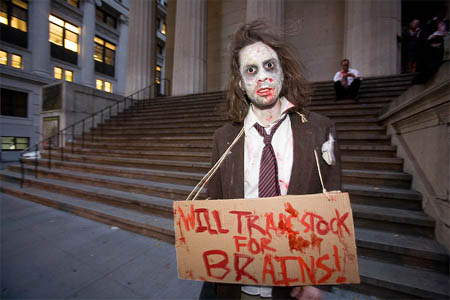

Neo-liberalism no longer ‘makes sense’, yet its logic keeps stumbling on zombie style. Just look at PFI schemes in the UK, where private finance is supposed to supply the money for government infrastructural spending, with the state renting back infrastructure for vast sums over a thirty-year period. Except now there is no private finance so the government has to lend banks the money to lend to private firms to build infrastructure, which it will then rent back to the state that lent the money in the first place. At every stage huge sums are skimmed off in to private hands. It doesn’t make sense yet the scheme is still being rolled out at the same rate it was before the crisis. There isn’t another logic or common sense to guide policy so neo-liberal logic is twisted through amazing contortions just to keep it all going.

Any new common sense, any new middle ground for politics, has lots of problems to overcome. It would have to operate in a similar multi-scalar fashion to neo-liberalism, that is, it would have to be tied to a new manner of living. It would also have the difficulty of starting from the composition we have now, with large parts of the world’s population still in the grip of neo-liberal common sense and modes of living. This is one of the greatest problems facing those advocating a New, New Deal. We aren’t talking about a few changes in elite thinking or some dabbling with government spending but the global re-composition of society.

Neo-liberalism is in crisis ideologically, it no longer ‘adds up’ on its own terms, yet it doesn’t seem to know it is dead. I could imagine it stumbling on for a considerable period, as no new middle ground is able to cohere and replace it. We face zombie-liberalism. This raises the prospect of no resolution being found for the crisis as we end up stuck in a long 10 or 20-year period of stagnation and drift. Even in its heyday neo-liberalism could actually be seen as a period of stagnation, it never reached anything like the growth levels of the post-war settlement years, but it still had its modernist side, the idea that neo-liberalism would solve the worlds problems. Without an overarching project we might just get a series of phoney recoveries, repeated crashes and a slow fragmentation, with some fractions of capital seeking to extend neo-liberalism and others trying to replace it but with nobody really succeeding.

3 Comments